The main church of Nicaea is not the same as the massive basilica that sank into Lake İznik, where the First Council of Nicaea was held in 325.

That one was built by Constantine the Great in the early 4th century, outside the city walls, by the lake, next to the so-called “Senate Palace,” the local hub of imperial administration, and dedicated to the local martyr Saint Neophytos, who was buried in the church’s sanctuary. It was probably chosen for the council because it was large enough to hold 200–300 participants.

The main church, however, stood in the center of the Hellenistic city, at the crossroads of the two main streets. An earlier church probably already stood there at the time of the First Council of Nicaea, but we know nothing about it. The current building’s first version was commissioned by Emperor Justinian (527–565), and dedicated to Hagia Sophia, just like the main church in Constantinople, also rebuilt by him.

The main church, however, stood in the center of the Hellenistic city, at the crossroads of the two main streets. An earlier church probably already stood there at the time of the First Council of Nicaea, but we know nothing about it. The current building’s first version was commissioned by Emperor Justinian (527–565), and dedicated to Hagia Sophia, just like the main church in Constantinople, also rebuilt by him.

Hagia Sophia – Ἁγία Σοφία τοῦ Θεοῦ, Holy Wisdom of God –, personified in Proverbs 8–9 and Wisdom 7–9 as חָכְמָה Chokmah, “Wisdom” – is understood in patristic and Orthodox tradition as Christ himself, as Saint Paul declares: “Christ is the power of God and the wisdom of God” (1 Cor 1:24). Saint Athanasius of Alexandria used this very identification at the Council of Nicaea to argue against the Arians, pointing out that Proverbs 8:22-32 presents Wisdom – that is, Christ, in Paul’s terms – as eternal. In this tradition, Christ, the Word made flesh, also embodies the wisdom of God’s salvific plan, and thus the Hagia Sophia churches were consecrated to Christ in recognition of his divine role as Savior.

Hagia Sophia – Ἁγία Σοφία τοῦ Θεοῦ, Holy Wisdom of God –, personified in Proverbs 8–9 and Wisdom 7–9 as חָכְמָה Chokmah, “Wisdom” – is understood in patristic and Orthodox tradition as Christ himself, as Saint Paul declares: “Christ is the power of God and the wisdom of God” (1 Cor 1:24). Saint Athanasius of Alexandria used this very identification at the Council of Nicaea to argue against the Arians, pointing out that Proverbs 8:22-32 presents Wisdom – that is, Christ, in Paul’s terms – as eternal. In this tradition, Christ, the Word made flesh, also embodies the wisdom of God’s salvific plan, and thus the Hagia Sophia churches were consecrated to Christ in recognition of his divine role as Savior.

Orthodox liturgy and iconography depict Divine Wisdom in many forms as Christ in God’s saving plan. Catholic iconography is less explicit; its most common formula is the medieval Madonna statue, with the blessing Jesus in her lap, often inscribed: “In gremio Matris sedet Sapientia Patris,” that is, “The Wisdom of the Father sits in the lap of the Mother.” The sanctuary of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople was decorated with a mosaic reflecting this union of Eastern and Western Wisdom traditions.

Orthodox liturgy and iconography depict Divine Wisdom in many forms as Christ in God’s saving plan. Catholic iconography is less explicit; its most common formula is the medieval Madonna statue, with the blessing Jesus in her lap, often inscribed: “In gremio Matris sedet Sapientia Patris,” that is, “The Wisdom of the Father sits in the lap of the Mother.” The sanctuary of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople was decorated with a mosaic reflecting this union of Eastern and Western Wisdom traditions.

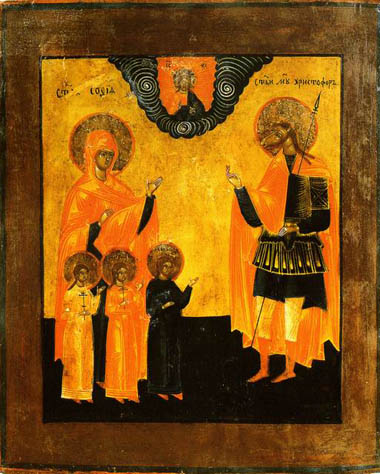

Interestingly, in Russian folk iconography, Hagia Sophia was depicted without theological complexity as “Saint Sophia the Great Martyr,” accompanied by her three daughters, Vera, Nadezhda, and Lyubov – Faith, Hope, and Love – who also fell victims to oppression, as it has often happened in Russian lands.

Exchange of experiences among apocryphal saints. Saint Sophia and her daughters in the company of the dog-headed Saint Christopher, whom we’ve already written about. 19th c., Moscow, State Historical Museum

Exchange of experiences among apocryphal saints. Saint Sophia and her daughters in the company of the dog-headed Saint Christopher, whom we’ve already written about. 19th c., Moscow, State Historical Museum

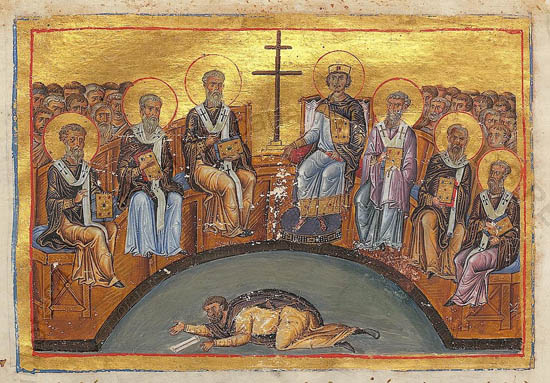

This church also hosted an ecumenical council: the Second Council of Nicaea, the seventh and final council of the undivided Eastern and Western Church in 787.

The council was convened by Empress Eirene, widow of Leo IV, and regent for her son, the underage Emperor Constantine VI, to settle the Byzantine iconoclastic controversy. The council originally met in Constantinople in 786, but the pro-iconoclast military blocked proceedings, so it was moved to Nicaea.

The council was convened by Empress Eirene, widow of Leo IV, and regent for her son, the underage Emperor Constantine VI, to settle the Byzantine iconoclastic controversy. The council originally met in Constantinople in 786, but the pro-iconoclast military blocked proceedings, so it was moved to Nicaea.

The council’s decree allowed veneration of icons, but not worship, which was reserved for God alone. It also declared that respect shown to an icon passes to its subject, so it cannot be considered idolatry – a stance later echoed by the Catholic Council of Trent (1545–63) against Protestant accusations of idol worship. The justification was not supported with Christological arguments, as in the 754 Council of Hieria, but based on the antiquity of image veneration and the incarnation of Christ, which makes His depiction possible.

The Second Council of Nicaea in the menologion of Basil II (976–1025), Vat. Gr. 1613 fol. 108. Center: Patriarch Tarasios and Emperor Constantine VI, on the ground a humiliated iconoclast

The Second Council of Nicaea in the menologion of Basil II (976–1025), Vat. Gr. 1613 fol. 108. Center: Patriarch Tarasios and Emperor Constantine VI, on the ground a humiliated iconoclast

Unfortunately, the council’s church hasn’t survived. The building was destroyed in an earthquake in 1065, after which the current structure was built.

The expanding Ottomans captured Nicaea in 1331, and as usual, the main church was converted into a mosque, named Orhan Djami after the conquering sultan. They also built a madrasa and a bathhouse, which have not survived.

Timur’s invasion in 1402 severely damaged the mosque, which suffered fire in the mid-15th century and later another earthquake. It stood in ruins for a century, likely washing away the interior Byzantine frescoes.

Photos by Guillaume Berggren, c. 1870–80, showing the northeastern apse and the interior

Photos by Guillaume Berggren, c. 1870–80, showing the northeastern apse and the interior

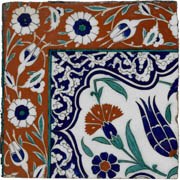

In the early 1500s, the Ottomans fought a two-century-long struggle against the rising Safavid Persian dynasty, mainly along the Ottoman-Persian frontier inhabited by Armenians and Kurds. Both sides often deported entire Armenian artisan communities to enrich their own territories. In 1515, Armenian potters from Tabriz were relocated to İznik (as the city name evolved from Greek eis Nikaia, “to Nicaea,” much like Istanbul from eis tan Polin, “to the City”).  Here they created the famous İznik tiles used throughout the empire, including the Blue Mosque in Istanbul, whose floral motifs even reached Transylvanian churches. The city entered a new golden age, and ruined buildings were rebuilt. The mosque was allegedly restored by Sinan under Sultan Suleiman’s commission.

Here they created the famous İznik tiles used throughout the empire, including the Blue Mosque in Istanbul, whose floral motifs even reached Transylvanian churches. The city entered a new golden age, and ruined buildings were rebuilt. The mosque was allegedly restored by Sinan under Sultan Suleiman’s commission.

During the 1920–22 Greco-Turkish war, the front line moved around Nicaea. Greek forces destroyed nearby Turkish villages, and incoming Turkish troops expelled most of the Greek population. By the end, 60–70% of the old town was in ruins, every church and monastery collapsed, and İznik ceramic art was destroyed. The displaced Greek population was replaced with Balkan Muslim refugees (muhacirs).

The damaged Hagia Sophia was turned into a museum by Atatürk in 1935. Like Istanbul’s Hagia Sophia or the Chora Church, this gesture symbolized the country’s secular turn and a reevaluation of its pre-Islamic, multi-layered past.

Archaeological research took place in 1935 and 1953, uncovering Byzantine mosaic floors and fresco remnants, and the exterior ground level was lowered two and a half meters to the foundations. The southern parekklesion (external chapel) mosaic floor was also revealed and is still shown, exposed to the elements, behind a protective iron grid.

Restoration began in 2007, including roof and dome reconstruction and rebuilding the minaret. Work was completed in 2011, and the building reopened… as a mosque for Kurban Bayramı, the Feast of Abraham’s Sacrifice.

This move was part of the country’s re-Islamization process, foreshadowing the later reconversion of Istanbul’s museum-mosques back into mosques. The decision sparked protests nationwide and internationally, and even some local Muslims opposed it, claiming there were already enough mosques in the city. But it went ahead. Today, the building still functions as a mosque, though during our one-hour visit we only saw a single worshipper, while about 20–30 mostly domestic tourists came to visit as a historic monument.

The lone worshipper arrives – the imam himself – who, praying throughout our visit, becomes an unavoidable but stylish background character in our photos with his white turban and beard, yellow shirt, and brown clerical robe.

The lone worshipper arrives – the imam himself – who, praying throughout our visit, becomes an unavoidable but stylish background character in our photos with his white turban and beard, yellow shirt, and brown clerical robe.

Entering the mosque, three steps lead down to the floor level, where a beautiful Byzantine floor mosaic was uncovered right in front of the entrance. Based on Italian cosmatesque examples, I’d date this to the 12th–13th centuries. However, in the main church of the Iviron Monastery on Mount Athos, a very similar floor mosaic was claimed to be from the 10th century.

One thing’s for sure: the lilies prominently framing the mosaic’s central section were the symbols of the Laskaris family, who ruled the Nicaean Empire between Venice’s occupation of Constantinople in 1204 and the Palaiologos restoration in 1261.

One thing’s for sure: the lilies prominently framing the mosaic’s central section were the symbols of the Laskaris family, who ruled the Nicaean Empire between Venice’s occupation of Constantinople in 1204 and the Palaiologos restoration in 1261.

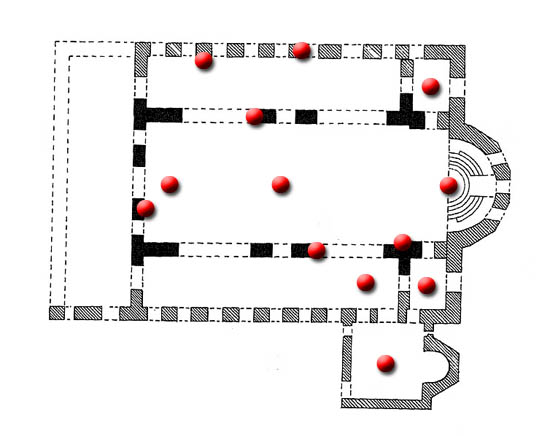

The church is a three-aisled basilica, with a very spacious central nave and narrow side aisles, a semicircular central apse, and straight-ended side apses – basically small square side rooms topped with tiny late-Byzantine domes.

During the mosque conversion, the mihrab, facing Mecca, and the minbar were installed in the southern side aisle.

The apse of the main sanctuary is filled with stepped tribunes, serving as seating for the clergy during the liturgy, similar to the Hagia Eirene in Constantinople. The floor is paved with stone mosaics, and in front, at the former altar location, a marble slab is set into the floor.

The sanctuary of Hagia Eirene in Constantinople with its stepped tribunes. In the next image, one can see that the altar there also stood on a recessed marble slab.

The sanctuary of Hagia Eirene in Constantinople with its stepped tribunes. In the next image, one can see that the altar there also stood on a recessed marble slab.

In the wall of the northern aisle, probably on the tympanum of a former gate, a Deesis fresco was uncovered in 1935, depicting the Virgin Mary and John the Baptist pleading before the half-length Pantokrator. This gate was likely bricked up early, which allowed the fresco to remain in good condition.

Further toward the sanctuary, the volute of an ancient marble Ionic capital remain embedded in the window reveals.

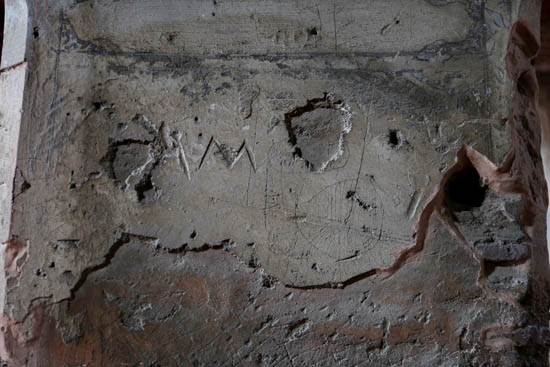

At the end of the northern aisle is a square room, the prothesis, used for preparing the liturgical bread and wine. Decorative elements have remained in the window reveals, along with outlines of three saints on the drum. Several small incised crosses from the period of iconoclasm, when these were the only permitted decorations, are still visible on the walls and vaults.

At the end of the southern aisle is a similarly square room, the diakonikon, used as the deacons’ vestry and for storing liturgical garments. On the floor along the southern wall is a marble sarcophagus. Above it, under the window, is a half-length angel on the left. Above and to the left and right of the window are two more half-length angels, the one on the right barely visible. The drum bears the outlines of two saints. These must have been clearly visible even when the building was converted into a mosque, as their heads were obviously smashed off with a hammer.

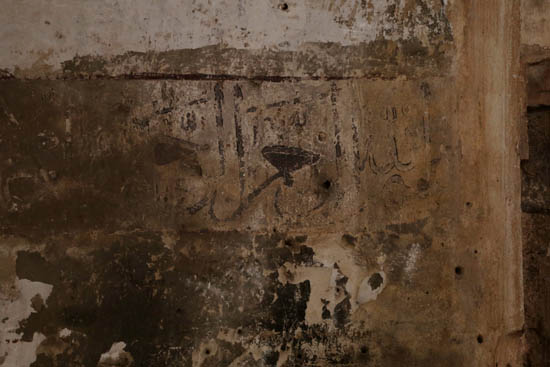

From the building’s earlier mosque phase, Arabic inscriptions and graffiti remain on the arches connecting the nave with the aisles and to the left of the entrance.

In summary, the church once boasted rich decoration: frescoes on the walls and stone mosaics on the floor. Most of this was likely lost not during the conversion to a mosque, but over the centuries when it stood roofless and in ruins. It is remarkable that so much survived under the protection of the arches.

It is equally remarkable that at least this one Byzantine church has survived more or less in its original form out of the twenty that once stood in Nicaea, and out of the many thousands across the country. Exactly this one, even converted into a mosque, which hosted the Second Council of Nicaea, and the other, even underwater, which hosted the First.

Add comment