The short video below was posted publicly on Instagram in early January, just a few days before the entire internet was shut down in Iran. In the footage, a young musician, Yâshâr Alipur plays the târ, the distinctively shaped Persian lute. According to the caption, the video was recorded the previous evening on the Tehran metro. Although the system tends to view buskers as little more than beggars at best, sound artist Vedâd Fâmurzâde was already writing about the growing presence of emerging and amateur musicians among street performers nearly a decade ago—back when the phenomenon itself was only five or six years old. So the context matters, of course, but even more telling than the street performance is the song the young man is playing.

The piece is a tasnif, a ballad-like song, with both lyrics and music by the poet and singer-songwriter Abolqâsem 'Âref Qazvini. It was composed during the Iranian Constitutional Revolution (1905–1911), more precisely in the period of the Second Parliament, sometime between 1909 and 1911. A patriotic song—like many of 'Âref’s tasnifs—yet this one became the most popular, especially from the 1950s and 60s onward. Over time it entered the repertoire of Persian classical (dastgâh) music, much like Dawn Bird, the similarly patriotic song by his contemporary and friend Mohammad-Taqi Bahâr, which we have written about before.

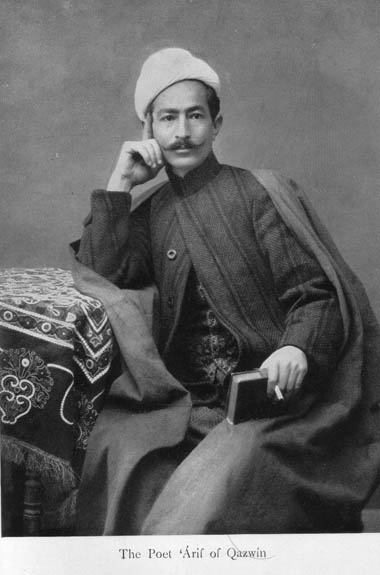

Around that time, in January 1913, the Iranist Edward G. Browne’s informant—later his assistant—the Istanbul-educated and widely travelled political activist Mirzâ Hossein Kâzimzâde described ’Âref as someone who has a “dervish-like disposition and often sings his poems to the accompaniment of music at public and patriotic meetings, where he is warmly applauded by all” (Edward G. Browne: The Press and Poetry of Modern Persia. Cambridge, 1914. xvi. p.).

’Âref’s father intended him for the clergy, but after moving to Tehran in 1898 his singing voice quickly caught the attention of the local elite and eventually of the shah, Mozaffar al-Din, whose court he joined for a time. He later became a supporter of the Constitutional Revolution. In 1921 he joined General Pessian, who proclaimed the short-lived Autonomous Government of Khorasan; after Pessian’s death he supported the future Reza Pahlavi. Perhaps owing to his difficult temperament, despite his popularity he died poor and alone at the age of fifty-two in Hamadan.

’Âref’s best-known portrait, from here

’Âref’s best-known portrait, from here

No recordings of ’Âref himself survive—though one of Tehran’s best instrument shops now bears his name—but we do have many performances by others, from Elahé to Parissa and—of course—Mohammad Reza Shajarian. As in so many cases, it was ultimately Shajarian’s version that became the best known.

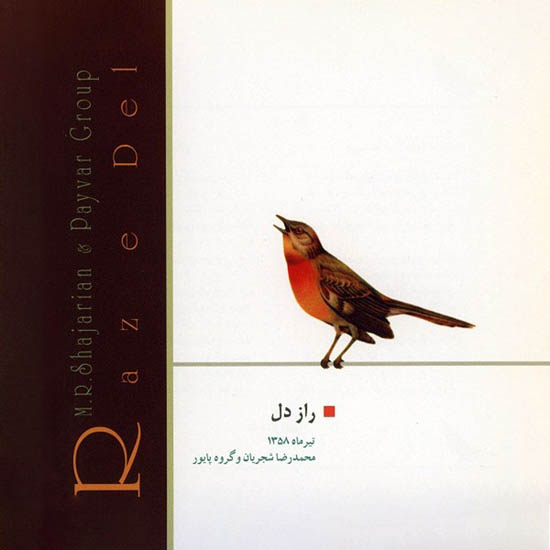

From the album راز دل Râz-e del (The Secret of the Heart, 1979), recorded with the Pâyvar Ensemble

|

هنگام می و فصل گل و گشت چمن شد |

hangâm-e mey o fasl-e gol o gasht-e chaman shod |

it is the season of wine, of roses, of walking in the meadows

the courtyard of spring is cleared of crows and ravens

because of the generous cloud, Rey has become the envy of Khotan *

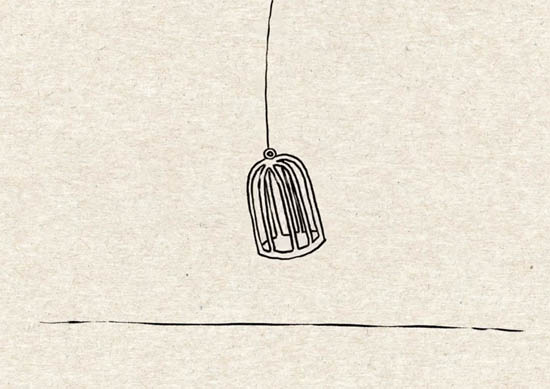

like me, the caged bird grows sorrowful for our homeland

how crooked you are, O fate! how wicked you are, O fate!

vengeful you are, O fate! you have no faith, no creed, O fate!

from the blood of the homeland’s youth the tulip springs forth

beneath the weight of mourning * even the cypress bends

from this sorrow the nightingale hides in the rose’s shade

and the rose, like me, tears its garment in grief

with all our tears turn the face of the earth upside down,

if you hold even a handful of your homeland’s soil, cast it upon your head

stand in defense [of the homeland] and prepare for darker days ahead

let your chest be a shield before the enemy’s arrow

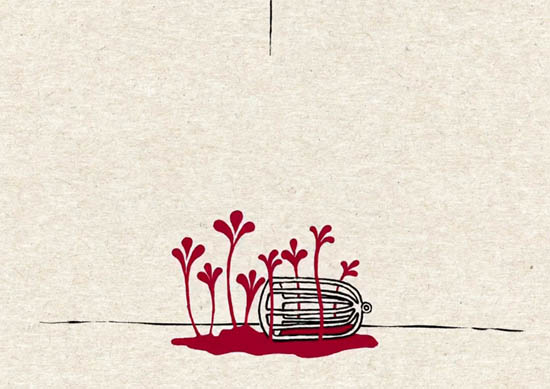

Its popularity is perhaps shown even more clearly by modern reinterpretations like that of the young musician playing in the metro. The full poem is rarely performed; most renditions include only a few of the above couplets—or even fewer. Presumably these lines retained their relevance over time, and perhaps because they draw most strongly on the well-known imagery of Persian poetry. The title line is arguably the most powerful. Although it is not heard in the metro recording mentioned above, anyone familiar with the melody will instantly recall it: از خون جوانان وطن لاله دمیده az khun-e javânân-e vatan lâle damide, “from the blood of the homeland’s youth the tulip springs forth.” The tulip—or imperial crown (Persian لاله واژگون lâle-ye vâzhgun, the inverted tulip)—is said in legend to grow from the spilled blood of the innocent mythical hero Siyâvash. As we have written before, the story of Siyâvash—told in The Book of Kings—and with it the tulip/imperial crown became a core Iranian symbol of oppressed yet reborn freedom, rising again from the blood of martyrs. ’Âref compresses all of this into a single line.

This image also holds the key to another aspect of the song’s popularity. Iran’s modern history has repeatedly unfolded in ways that made this line—together with the longing for dawn—feel painfully current again and again. Perhaps never more so than in recent weeks, following the brutally violent suppression of the protests that had been ongoing since late December.

Animation by Maryam Sidayat from here

Animation by Maryam Sidayat from here

The song carries real weight—so it was no coincidence that this was the piece heard on the Tehran metro at that moment. Nor only there: before the blackout I saw other musicians inside Iran performing it as well (and afterward, members of the diaspora continued to do so). “These days this is what I find myself humming,” wrote one of them, barely a day before Iran was cut off from the outside world. One can only hope that the long-awaited dawn will finally arrive—and that the imperial crowns will not bloom in vain.

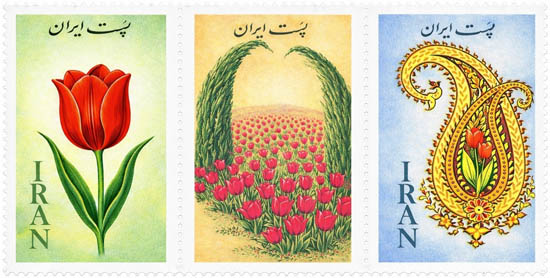

Preparing for the soon-approaching Persian New Year. A reimagined and updated version of the fifty-one-year-old (1975 / 1354) New Year stamp series: the central stamp beautifully illustrates the famous couplet mentioned above. Graphic by Mehrdad Aref-Adib, from here. Only after finishing this post did I notice that he also recently wrote a short piece about this tasnif.

Preparing for the soon-approaching Persian New Year. A reimagined and updated version of the fifty-one-year-old (1975 / 1354) New Year stamp series: the central stamp beautifully illustrates the famous couplet mentioned above. Graphic by Mehrdad Aref-Adib, from here. Only after finishing this post did I notice that he also recently wrote a short piece about this tasnif.

Add comment