According to the old rule, a medieval building or city can remain strikingly authentic if it was built in a period of prosperity but then fell into poverty in modern times—leaving no money for fashionable rebuilding. This rule applies perfectly to Nicaea. The city walls were erected during the Roman Imperial period, when Nicaea was an imperial city and a major council seat. After the Ottoman conquest in 1331, however, it became a small provincial town. As a result, its walls survived almost intact: nearly five kilometers long, with close to a hundred towers and four monumental gates.

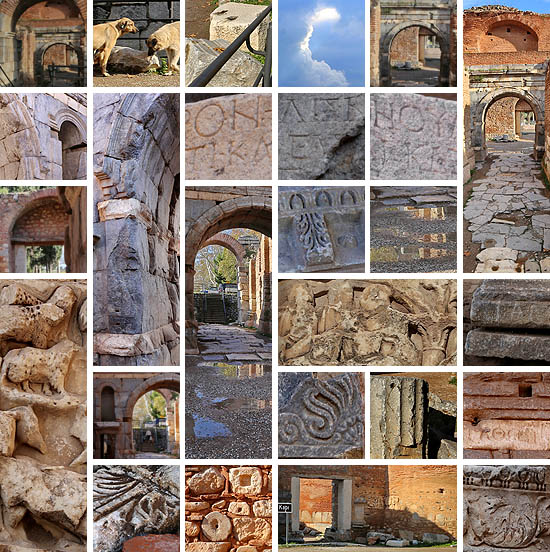

Founded in 316 BC, Nicaea was surrounded by its present circuit of walls after the Gothic invasions of AD 258. From the 4th century onward—when an imperial palace was built here and the city became a conciliar center—the walls were raised and reinforced several times, and restored after major earthquakes (368, 557). After 1204, when Constantinople fell under Venetian occupation, Nicaea became the capital of what remained of the Byzantine Empire, the Empire of Nicaea. At this point the fortifications were massively strengthened, including the construction of a second, outer wall, richly spolia-filled with fragments of ancient buildings and sculptures. When Orhan Ghazi, the second Ottoman sultan, incorporated the city into the Ottoman state in 1331, the defensive role of the walls gradually faded; they became customs checkpoints and ceremonial monuments instead. As the population shrank from 20–30,000 in antiquity to barely 1–2,000 by the 18th–19th centuries, the town—almost a village by then—had ample ruins available for new construction, and no need to dismantle the walls. Thus they survived nearly in their entirety, left mostly to the slow work of time.

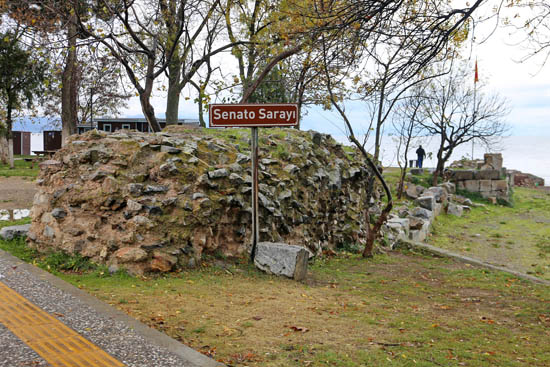

Most visitors begin their exploration of Nicaea with its most famous monument, the submerged basilica. Nearby, on the lakeshore, stand ruins marked today as the “Senate Palace.” If the identification is correct, it was not in the city center but here, by the water, that the municipal headquarters of the polis once stood—possibly hosting some sessions of the First Council of Nicaea in 325.

A little north of the palace stood the city’s western gate, the Porta Lacus, or Πύλη τῆς Λίμνης, today still known as the Göl Kapısı, the Lake Gate. This is the worst preserved of Nicaea’s gates, and probably always the least impressive and least fortified. On this side, the lake itself provided natural defense, and unlike the other three gates, this one served economic rather than representational purposes: fishing, transport, warehouses. Accordingly, it was the widest of the four. Today only the remains of two towers survive, flanking the modern street.

From the gate, Kılıçaslan Caddesi leads toward the center. The street is named after the Seljuk sultan Kılıç Arslan I (1091–1107), “Lion of the Sword,” who ruled Nicaea as a Seljuk capital during the First Crusade. In antiquity, this was likely the main street of the Roman city: the Cardo, Via Principalis or Via Regia, Κεντρικὴ ὁδός or Βασιλικὴ ὁδός. At its intersection with today’s Atatürk Caddesi—almost certainly the ancient Decumanus or Platea minor, Ὁδός μικρὰ—stands the former Hagia Sophia, once the city’s main church and today the Great Mosque, where the Second Council of Nicaea was held in 787.

Facing the church stands a far more prosaic but no less appealing institution for today’s traveler: the Kenan eatery, offering excellent and inexpensive Turkish dishes—ideal fuel for a full day of walking around the city.

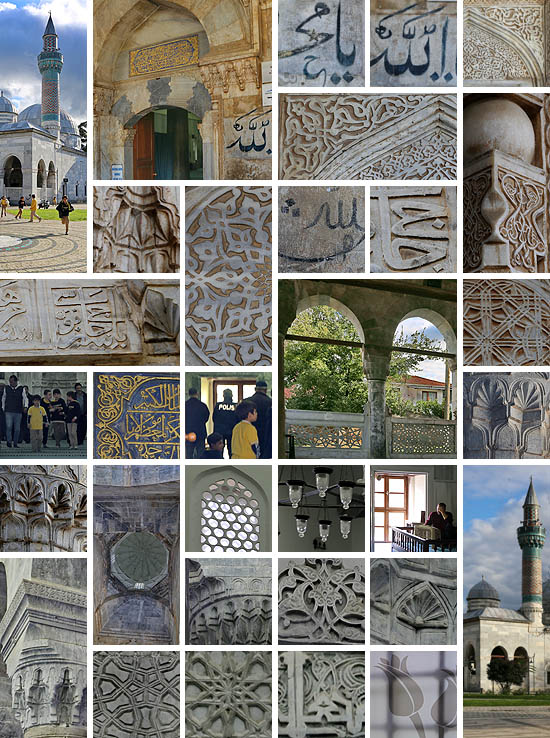

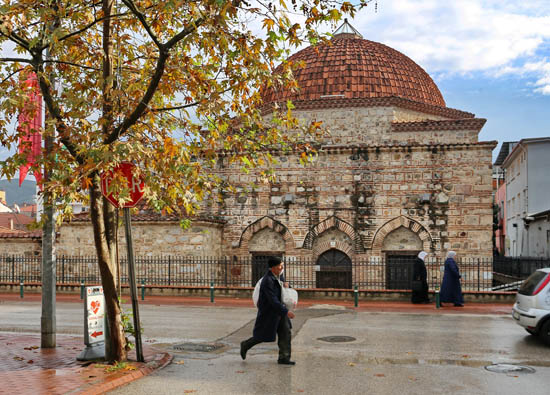

Heading north along the former decumanus, we soon reach the city’s oldest bathhouse, the Murad I or Great Bath. Its two domes once covered separate men’s and women’s sections. Built between 1450 and 1500, it now serves as a museum. Next to it, a section of an ancient colonnaded stoa was uncovered in 2007. In its courtyard operates a ceramic bazaar whose tourist wares—like those in the city’s other ceramic shops—borrow the name of the famous İznik pottery tradition that definitively ended around 1920.

Continuing on, we reach the northern Istanbul Gate – Porta Constantinopolitana, Πόρτα Κωνσταντινουπόλεως. It was originally conceived as a triumphal arch-like ceremonial gate, but was later reinforced several times. In its 13th-century outer wall, two marble reliefs were reused as spolia, probably fragments of an earlier triumphal arch. Numerous other ancient architectural fragments can be seen scattered throughout the outer wall and around the fortifications.

At the southern end of the decumanus opens the Yenişehir Gate, known in antiquity as Porta Neapolis, Πόρτα Νεάπολις. Like its northern counterpart, it began life as a triumphal arch and was later reinforced several times. Its 13th-century outer wall was equipped with a large circular bastion.

Next to the gate, on the other side of the road, stands one of the city’s most bewildering sights. The squat building – a transformer station – is topped with the double-headed Greek imperial eagle, lined with a two-row Greek inscription below, and at the very bottom, Turkish warriors with shields and helmets march in. You might think the Greek army of the 1920s built or at least painted it with royal Greek emblems and inscriptions, and that the Turks – with remarkable wit – didn’t destroy it, but rather made themselves part of the scene, marching into the Greek city.

But the Greek inscription tells a different story:

“A building belonging to the province of the city of Nicaea in honor of the emperors. Erected by Bateskyes, Kassios, Oristos, M. Plankios”

This inscription appears elsewhere in the city, but from the late 2nd century. Over the fourth gate, the Lefke Gate. The plural “emperors” refers to the joint rule of Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus, 161–169, during a restoration when Nicaea and the entire province of Bithynia were prime building zones. So the decoration is modern, depicting the Ottoman army entering conquered Nicaea through the Lefke Gate in 1331.

And just outside the Yenişehir Gate, there’s another monument dedicated to the conquest. A türbe with six green tombstones inside, covered with colorful Central Asian rugs. In front of the türbe stands a modern statue: a warrior with a Mongoloid face, fierce expression, and muscular arms crossed.

According to the inscription, Orhan Ghazi erected the türbe for the “Kyrgyz” warriors who participated in the capture of Nicaea in 1331. Modern research suggests that “Kyrgyz” didn’t refer to a specific people at the time – who would only emerge in the 17th–18th centuries – but generally meant Central Asian Turkic warriors. The Kyrgyz Consulate in Bursa, however, took this site under their wing, commissioning the statue by sculptor Turgunbay Sadykov and planting commemorative trees around it.

The main street from the main church/great mosque leads straight to the fourth gate. Lined with cafés and pastry shops, this street buzzes with the entire city, and on Monday late mornings, the city’s men are parked here, chatting and watching the world go by. The street is also home to pottery shops trying their luck off the fame of İznik ceramics. Towards the end of the street, right before the gate, stands the Antik Kafe—a sort of hip, vintage café styled like a caravanserai, complete with retro knick-knacks and sculptures.

On the north side of the street, the city’s first Muslim quarter likely arose after the conquest in what was a Greek-majority city until 1920. Evidence of this is the squat Haci Özbek Mosque, built in 1332 according to its inscription, right after the conquest.

Next to it, there’s a cemetery built by the sons of Çandarlı Halil Pasha for their father and family. The Çandarlı clan, rulers of İznik, were a very prestigious Turkish family, second only to the Ottoman dynasty. For seventy years, grand viziers came from this family. The last in line was Halil Pasha, buried here according to tradition. He opposed the siege of Constantinople, favored a deal with the Greeks, and reportedly accepted bribes from them. After the siege, Mehmed II had him executed. His sons returned to their estates in İznik, but the family thereafter played only a provincial role.

Next to the tomb, a few ancient columns and cornice fragments casually lie around—the ruins of the Great Bath, now a cat hangout. From here, a footpath leads north behind the street to the real heart of the Muslim quarter, where three important early Muslim buildings stand. The first is the 15th-century mosque named after the Quranic scholar Seyh Kutbuddinzade Mehmet, the second is the Nilüfer Hatun soup kitchen and guesthouse, built in 1388 by Sultan Murad I in memory of his mother, now the city Archaeology Museum.

The third is İznik’s pride, the Green Mosque. Built by Çandarlı Kara Halil Hayrettin Pasha, grand vizier to Murad I, between 1378-1391, it was the second mosque in İznik after the Haci Özbek Mosque and imitates its distinctive vault. It also served as a model for the mosques in Bursa and the first ones in Constantinople. Likely, carved stones from a Byzantine church once standing here were reused. Its name comes from the green and blue glazed tiles decorating the minaret.

The street runs straight to the Lefke Gate, which was the city’s second major gate after the Constantinople Gate. The Turkish name comes from the original Greek “White Gate” – Λευκὴ Πύλη. It was originally a triumphal arch, built in honor of Emperor Hadrian according to a fragment of its inscription, but over time it was reinforced multiple times, incorporating countless ancient stone fragments.

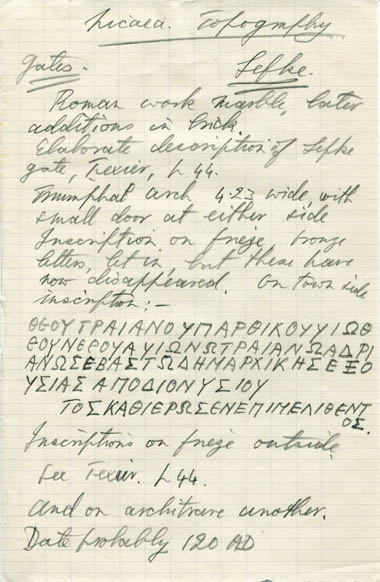

On the city-facing side of the earliest triumphal-arch gate, a Greek foundation inscription was carved. Today it survives only in fragments, but fortunately David Talbot-Rice, the great Oxford Byzantinist (1903–1972), still saw it intact and recorded it:

Θεοῦ Τραϊανοῦ Παρθικού υἱοῦ Θεοῦ Νέρου αἰῶνα Τραϊανῶ Ἀδριανῶ Σεβαστῶ δημοχικῆς ἐξουσίας ἀμοδιονυσίου τὸς καθιερός ἐνεμιμελιθέντος

“To the divine Trajan Parthicus, [adopted] son of the divine Nerva, Trajan Hadrian Augustus, holder of tribunician power. Under the careful supervision of the official Amodionysios, the dedication was duly carried out.”

Trajan’s title “Parthicus,” meaning “conqueror of the Parthians,” indicates that the inscription must date from after AD 117.

Here at the Lefke Gate, the aqueduct bringing water from the Bithynian hills entered the city. By the 19th century, the aqueduct was probably already in ruins, because in Charles Texier’s 1882 engraving, water is shown pouring from it. The puddle is still there today, with cars and motorcycles splashing through up to their bellies as they cross under the aqueduct.

Outside the gate stretches the İznik Muslim cemetery. Or rather, *the* cemetery, since the pre-1920 Greek-majority Christian cemetery was destroyed by the invading Turkish forces.

You can also tell from the graves that İznik’s Turkish population is relatively recent: most of the graves are modern, and even the oldest date back only to the 1930s. I didn’t come across any Ottoman-Arab inscriptions, i.e., pre-1928 alphabet change, among them.

The oldest and most impressive tomb is in the Hayrettin türbe, which consists of two domed chambers. It belongs to Çandarlı Kara Halil Hayrettin Pasha, the founder of the Green Mosque. As Grand Vizier under Sultan Murad I (1364), he was the first in his clan to hold office until his death in 1387, followed by his two sons, Ali and Ibrahim, and then their sons, up until Halil Pasha, who was executed in 1453. Next to his beautifully carved tomb is his son Ali’s, and around them are other family members, all adorned with exquisite 15th-century thuluth and naskh calligraphy.

Across the road next to the cemetery stands a solitary türbe containing a single tomb covered with Turkish flags, whose inscription identifies it as belonging to Sarı Saltuk.

Sarı Saltuk Baba was a highly renowned 13th-century Alevi dervish, mentioned by both Ibn Battuta and Evliya Çelebi; according to the former he was a Crimean Tatar, according to the latter his original name was Mehmed and he came from Bukhara. He was especially popular in the Balkans, where he was seen as a key figure in Islamic missionary work. His story was told in a thousand versions, collected in the Saltukname. In many places he was identified with local Christian saints – in Corfu with Saint Spyridon, in Ohrid with Saint Naum – and the local Muslims venerated Sarı Saltuk at these graves. He also had his own tombs, for example in Babadag, Dobrudja, which became an important Muslim pilgrimage site, named Baba-Dağ, “Father’s Mountain,” after him. Here in İznik he also has a tomb. Perhaps it was established by Muslims resettled from the Balkans in 1924, but it is certainly popular among the locals. While we were there, two cars stopped, women got out, approached the tomb, and prayed.

After the cemetery, we encounter an example of the tragically comic Turkish traffic planning, familiar yet always astonishing. The city’s ring expressway passes above the cemetery, and from it a sleek, newly paved exit arcs down, which… ends abruptly at the old, poor road next to the cemetery, like a river dying in the desert.

The road next to the cemetery continues winding through olive groves up the hillside, where another tomb stands – the oldest of all. Locals, God knows why, call it the Berber Kaya Lahdi, “Barber Sarcophagus.” Research shows it belonged to King Prusias II of Bithynia (182–149 BCE). Prusias was killed by his own son Nicomedes, and his tomb fared no better: shattered and covered with graffiti, it stands above Nicea.

From this tomb there is a magnificent view over the city, nestled among the lake and olive groves. The city’s silhouette is edged with the domes and minarets of numerous mosques; none of the original twenty Orthodox churches and monasteries remain. One thousand seven hundred years after the council, Arianism scored a crushing victory in Nicaea.

Add comment