The Turkish archaeology journals, with poor timing, reported on the discovery of the 3rd-century Good Shepherd fresco in Nicaea last December—just after I had already left the city. So I planned that now, being back in Nicaea, I’d go see it in person at the ancient Hisardere necropolis.

The village of Hisardere sits in the mountains, about ten kilometers northeast of Nicaea. Its Turkish name means “Fort Valley,” although there’s no castle ruin in the area. Of course, that doesn’t mean much: according to 16th–17th century Ottoman tax registers, the Samanlı mountains above Nicaea were full of small settlements, monasteries, hermitages, and Byzantine watchtower ruins—most of which have now vanished, or survive only in traces that experts spot and report about on Turkish and Greek hiking blogs and Facebook posts.

I can’t find the village’s old Greek name. There must have been one, since these villages above Nicaea were largely Greek-speaking until the Greco-Turkish war of 1920, and sometimes even until the population exchange of 1923.

At the village entrance, there’s a cemetery. It’s not the necropolis, but I stop to take a look—cemeteries always offer historical insights alongside their unique beauty. Most of the graves are marked by a single standing stone, sometimes pointed, without inscriptions, following Eastern tradition—while the family is alive, everyone knows who rests there; once the family is gone, who would care?

I find only one traditionally carved Ottoman gravestone, with a turbaned head, suggesting it marks a military officer. Soldiers must always wear the six-foot cloth they’ll be buried in, since they never know where sudden death might find them. Officers’ gravestones end in the shape of a fez, while women’s graves are adorned with curling rose vines—usually one rose for each child the deceased had.

In other former mixed villages nearby—more of which we’ll see—there are far more traditional carved gravestones. This solitary stone perhaps hints at the small pre-1923 Muslim population. Likewise, the dates of the modern inscribed tombstones start around 1950—that is, when the generation resettled from Greece passed away.

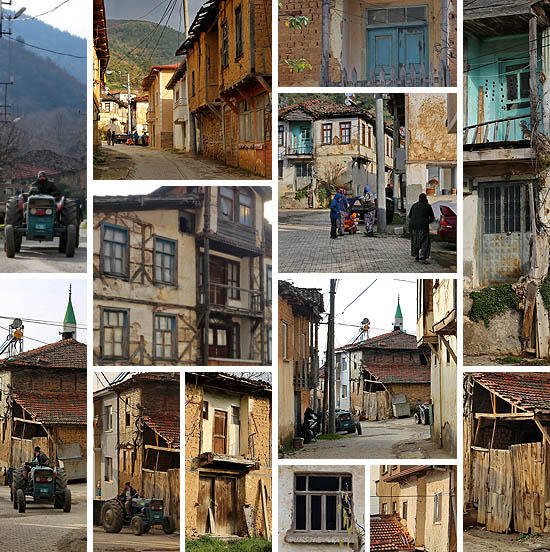

I walk into the village. It’s still traditional, with many old Ottoman-style timber-frame-and-adobe houses. These are the kind built by wealthy owners, which fell into modest use over time as funds ran out for renovations, and so remain. This might also indicate that poor Thessalian refugees settled into once-prosperous Greek homesteads. Some old houses stand empty, heading slowly toward decay. I may be seeing this village in its last moments—long gone elsewhere before I arrived.

On one corner of a house, a large ancient marble column is half-buried in the ground, probably to stop tractors from clipping the house corner when turning from the side street. My heart skips: this must come from that place. I have to ask here.

“Where is the ancient necropolis?” They don’t understand nekropol, so I try “cemetery.” Then they point toward the cemetery I saw earlier. “No, not that one. A very old cemetery, with underground tombs. Archaeologists are working there.” They send me to the young owner of the house, fixing his tractor in the barn. Surprisingly well-informed. “The necropolis isn’t here, it’s halfway between Nicaea and the village, among the olive groves, opposite the big cave.” He even shows it on Google Maps. “Can it be visited?” “I don’t think so. It’s fenced off and monitored by cameras. But whatever they found of value is displayed in the new museum.”

The muezzin calls. The dog lying in the neighboring yard lifts its head, adding a mournful second voice. In Turkey, I’ve often noticed dogs joining in the call, as if complaining to Allah for having made them impure.

Passing the mosque, the mosque attendant notices my camera and asks me to take a photo—first a close-up, then with the village panorama behind. I take his address to send him a printed copy.

I head back toward Nicaea. The large cave signals from afar that I’m in the right place. The excavation is exactly where the boy marked it on the map. No one is there, but cameras are watching. I photograph the first trenches through the fence; they stretch deep toward the back of the site.

Later, checking the Turkish press, I learned that in 2014 the police, while searching for a stolen car, noticed illegal excavations on the site. They alerted the heritage authorities, who then discovered the necropolis. Right from the first finds—three late Hellenistic sarcophagi—it was clear these were exceptionally valuable, so the city decided to build a new, modern museum—replacing the old city museum that had been housed in the 1398 Nilüfer pilgrim house and soup kitchen—, with these sarcophagi at the center of attention.

The museum, opened in 2023, is truly ultra-modern, following the general trend of contemporary Turkish museums. It has a rich collection of ancient and medieval artifacts, which I’ll write more about later. Its one major drawback is the lighting: the glare makes it almost impossible to photograph properly, with some details overexposed and others in deep shadow. The good photos you see online were mostly taken in the old museum courtyard, where the sarcophagi were temporarily displayed.

The innermost room of the museum’s labyrinth is devoted to the sarcophagi, with the centerpiece being the most beautiful of them all—the so-called Achilles sarcophagus. Its name doesn’t come from whoever may be buried inside, like Attila’s coffin or the Istanbul Archaeological Museum’s “Alexander the Great sarcophagus,” but from its decoration.

The main panel of the sarcophagus depicts the scene from Achilles’ story that opens the Iliad: when he takes offense—and withdraws from battle—because Agamemnon takes away his beautiful captive, Briseis of Lyrnessus, whose family he himself had slaughtered during the sack of towns around Troy.

|

Μῆνιν ἄειδε, θεά, Πηληϊάδεω Ἀχιλῆος |

Wrath—sing it, goddess—the wrath of Achilles, son of Peleus, / that brought countless sorrows upon the Achaeans, / hurled many valiant souls down into Hades, / and left their bodies as prey for dogs. |

Iliad, 1,1-4

In the center, Briseis sits on a chair, while Agamemnon’s envoy touches her shoulder, signaling her to follow. Don’t be misled by her central position—this is just a narrative requirement. The story, like in the Iliad, is seen from Achilles’ perspective. By being captured, Briseis was objectified, a “speaking tool,” a sexual slave, and this was considered natural at the time—by both the Iliad’s narrator and the sarcophagus master. Only modern novels give voice to the perspectives of Briseis and the other abducted Trojan women, like Pat Barker’s The Silence of the Girls (2018), Natalie Haynes’ A Thousand Ships (2019), or Emily Hauser’s For the Most Beautiful (2016).

The sides of the sarcophagus are divided by columns, with the longer sides split into five “windows” and the narrower ones into three, each filled with a figure. This design was especially popular in 2nd–3rd century Asia Minor. The sarcophagus was carved from the period’s favored Docimium marble, quarried near today’s Afyonkarahisar, halfway between Smyrna and Ankara, and exported in large quantities to Egypt and Rome (even the Pantheon’s white marble inlays came from this stone).

Achilles is depicted on other sarcophagi too, but far more explicitly connected to death: mourning Patroclus, killing Hector, or dying himself, full of pathos and dynamic movement. This style was popular in the western, Latin half of the empire. The Greek communities in Asia Minor preferred a stoic, psychological approach. Here Achilles sits at the far left, holding a weapon but naked, showing complete self-control in the face of the injustice done to him—as fate had been unjust to the dead and their loved ones. His nudity, in the visual language of the time, is so-called heroic nudity, drawing attention to his character, and his arete, masculine virtue. The depiction transforms the epic hero into an ethical one, thereby also positioning both the dead and the survivors as heroes who bear loss with great self-discipline. The representation is not about death, but about the virtues and dignity of the deceased and their family. Roman depictions say, “This is how a hero dies.” The Asia Minor Greeks say, “This is how a hero lives.”

Between Achilles and Briseis, we see a messenger explaining to Achilles—probably Odysseus, sent first by Agamemnon to claim the girl. To Briseis’ right, the second messenger, Ajax, touches her shoulder, summoning her to follow. On the far right stands a third, older messenger, Phoenix, Achilles’ former tutor, sent specifically by Agamemnon to persuade the hero. Notably, Phoenix does nothing, makes no argument—he just stands, as if fully aware of the injustice, acting as a model for the viewer within the image.

One figure is missing from the composition: Agamemnon, who elsewhere appears as a commanding presence in Briseis scenes. His absence here emphasizes the impersonality and inevitability of injustice.

Briseis appears only as an object, a secondary figure, but at one point the viewer can still identify with her. When Ajax touches her shoulder, compelling her to follow—a gesture also used in other sarcophagi to signal a summons to death.

On the other long side of the sarcophagus stand five young, naked men. These are the Myrmidons, Achilles’ warriors, usually depicted fighting. Here they embody the same still, restrained strength as Achilles on the opposite side. And just as Agamemnon does not appear there, their leader, Achilles, is also absent here, who would otherwise animate them. For a contemporary viewer used to images of fighting Myrmidons, this stillness is meaningful and reinforces the stoic lesson of the opposite side.

On the two shorter sides, three women each stand between columns, holding fruit or severed animal limbs—in short, sacrificial offerings. These are the Horae, personifications of time and the cosmic order, suggesting that the hero’s fate is embedded in the world’s order.

The sarcophagus’ four-sided cycle thus creates a stoic ethical model, familiar and convincing to contemporary Greek viewers. It frames the injustice of death within the order of the world and teaches acceptance. It differentiates between the excited, arguing messenger and the calm, silent hero. And—in a way unusual for the time—it even allows for identification with Briseis.

I couldn’t see the Good Shepherd fresco, but I did learn how, when Nicaean Christians buried under his protection, a pagan citizen in the same necropolis related to death.

At the discovery of the Achilles sarcophagus in the Hisardere necropolis

At the discovery of the Achilles sarcophagus in the Hisardere necropolis

Add comment