The title, as I learned from the post, is a pleonasm, since there is no such thing as a fish that is not from the sea—or if there is, it is not worth to mention. The post was written for my birthday by Wang Wei, and I translated it from the Spanish–Catalan surzhik into languages that are easier to understand. From the tautology of “sea fish” the text moves in a straight line to fish falling from the sky, and even to fish so much in love that they forget how to swim, and above all to the sad, blood-soaked story of the whale that ran aground off the coast of Mallorca—a story whose political overtones, framed by Franco’s death, are given their key by Béla Tarr. And all the while—this is the island’s universe—we have traveled only a few miles, from the Varadero fish bar in Palma to the harbor of Colònia de Sant Pere.

When Tamás comes to Palma, we perform two rituals that guarantee the happiness of the days we will spend together. First, on the way from the airport to home, we stop at the Varadero to have a beer, looking at the Cathedral and Palma’s skyline from what was once the old Passeig de la Riba.

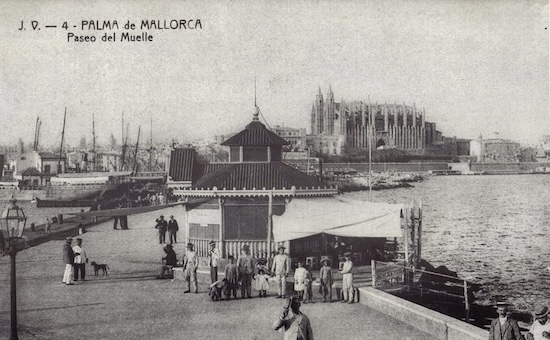

The breakwater built in front of the Almudaina Palace gradually turned into the “Passeig de la Riba,” a favorite spot for the people of Palma because it was a seaward extension of the Born. A kiosk was soon added, which became a popular meeting place (below). Today, buses bring cruise-ship tourists here to begin their visit to the city. This photo was taken where the Varadero bar now stands.

The breakwater built in front of the Almudaina Palace gradually turned into the “Passeig de la Riba,” a favorite spot for the people of Palma because it was a seaward extension of the Born. A kiosk was soon added, which became a popular meeting place (below). Today, buses bring cruise-ship tourists here to begin their visit to the city. This photo was taken where the Varadero bar now stands.

Over time, the promenade kept expanding. Behind the photographer stood the “far de la Riba” lighthouse (from Fotos Antiguas de Mallorca).

Over time, the promenade kept expanding. Behind the photographer stood the “far de la Riba” lighthouse (from Fotos Antiguas de Mallorca).

The second ritual, also with a maritime theme, is to ask him—rhetorically—“What do you feel like eating?”, to which the answer is invariably: “A sea fish!” Perhaps gluttony briefly dulls Tamás’s famously sharp linguistic sensitivity, and he fails to notice the pleonasm of saying “sea fish” in Mallorca—as if the Danube reached this far, or as if he were lugging Lake Balaton along with him. I would swear it is impossible to buy fresh fish in Mallorca that does not come from the sea, and some Mallorcans probably don’t even realize that in those strange, bland inland waters there might be anything edible at all.

By contrast, many years ago I traveled to Budapest carrying a bit of the sea with me. It was two large boxes of sea bream that I smuggled in. At 6:30 in the morning I went to the Mercat de l’Olivar and bought eight portion-sized sea bream, got hold of two polystyrene boxes from the clinical analysis lab of Palma’s main hospital, had them filled halfway with the dry ice used to transport medical samples, placed four bream in each box, wrapped everything up with duct tape, and went to the airport with them as if they were just two more suitcases. The conveyor belt swallowed them whole, and the bream traveled happily without a single jolt or the need to show a passport in the cargo hold of a Wizzair plane. I was convinced I would never see them again, but they turned up intact at baggage claim at Budapest airport. And not only did I see them—we devoured them that very night, cooked Mallorcan-style in Tamás’s home oven.

A far greater feat than mine, of course, was that of the circus director who transported a whale to the Hungarian plain to exhibit it while it slowly rotted in the trailer of a huge truck (there are no polystyrene boxes that big, nor enough ice). In that case, however, the presence of the marine animal ended up triggering a dark outbreak of extreme violence among the villagers. The unsettling story was filmed by Béla Tarr in Werckmeister Harmonies (screenplay by László Krasznahorkai, 2000).

Marine animals have obscure habits and sometimes behave capriciously, coming and going without anyone having to instruct them or tell them where to go. A species disappears from the fishing grounds and not a single fry is caught—until, just as unexpectedly, they reappear and fill the fishermen’s nets.

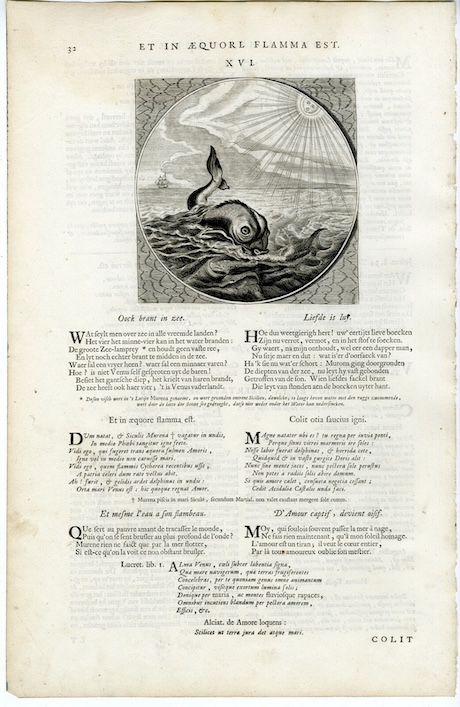

And some fish even fall so wildly in love that they lose the will to keep swimming. Alle de Wercken van den heere Jacob Cats, 1655, p. 32

And some fish even fall so wildly in love that they lose the will to keep swimming. Alle de Wercken van den heere Jacob Cats, 1655, p. 32

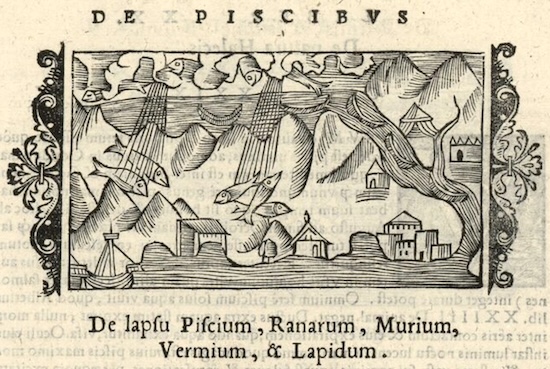

Sometimes fish even come down on us in the form of rain, as Seneca marveled in his Naturales Quaestiones (“Quid quod saepe pisces quoque pluere visum est?…” [Why do people often see fish falling from the sky?], I, 6, 2–4), or Athenaeus in the Deipnosophistae (“Ferunt etiam pisces de caelo decidisse, ut in Paeonia et in Dardania, atque in regione Chaeroneae…” [They say that there have been times when fish have fallen from the sky], VII, 331e–f); and then, in their wake, so many tales steeped in mirabilia from the Middle Ages to the Baroque: Isidore of Seville (Etymologiae XIII, 7, 7), Albertus Magnus, Cardano, Kircher… Or, for example, Olaus Magnus in his book on the unexplored regions of the North (1555):

Olaus Magnus, Historia de gentibus septentrionalibus, lib. XX. “De piscibus” – Cap. XXX. “De lapsu Piscium, Ranarum, Murium, Vermium, & Lapidum”, p. 726

Olaus Magnus, Historia de gentibus septentrionalibus, lib. XX. “De piscibus” – Cap. XXX. “De lapsu Piscium, Ranarum, Murium, Vermium, & Lapidum”, p. 726

As far as I know, whales have never rained down from the sky. But it is well known that these animals are prone to startling coastal populations by unexpectedly appearing on beaches and, often, choosing a populated area to spend their final hours and die there, to the horror of the onlookers. One of the most interesting stories of this kind may be that of the beast whom the subjects of Justinian I (527–565) christened Porphyrios, and which terrorized all ships approaching Constantinople for more than sixty years. Procopius of Caesarea tells the story in his Secret History and in the History of the Wars *, giving details of its enormous size and ferocity. Porphyrios attacked fishermen and warships alike, sinking them with a single swipe of its tail. Despite attempts to destroy it promoted by the emperor himself (who, regrettably, did not think of praying to Saint Raphael of Ethiopia), Porphyrios only ceased its depredations on the day it ran aground in muddy shallows at the entrance to the Black Sea while chasing dolphins and was unable to return to deeper waters. Alerted locals rushed to the spot with axes and knives, but with these tools they could barely pierce its skin. In the end they managed to bind it and painfully drag it ashore, where they hacked it to pieces and many of them, right there on the spot, threw a cheerful and extremely abundant barbecue. One may doubt whether this beast was really Porphyrios, but the fact remains that from that day on no other whale ever terrorized the Bosphorus.

There are some curious constants in modern literature when stranded whales or whale carcasses appear—immense animals decomposing with no one knowing how to get rid of them. They are often turned into symbols of a power in decay, or of a social situation marked by simmering, irresolvable tensions that can scarcely be put into words, and whose latent presence irreversibly poisons the air and coexistence. This is the anguished weight of Béla Tarr’s film, and it is also there—on a lesser scale and wrapped in his characteristic irony—in Eduardo Mendoza’s story La ballena (from the volume Tres vidas de santos, 2009), with a dead whale in the port of Barcelona in the late 1950s.

And it is also the distant backdrop of a more immediate story that I now wanted to recall.

Colònia de Sant Pere, Artà, in the early 1970s. This is how Rafel Ginard saw it in his Croquis artanencs (1929): “… a wretched little place of tiny houses, fairground or nativity-scene huts, poor and miserable, with thin and meagre soil, where only tamarisks and a little vine manage to thrive, with scarcely any wealth beyond salty wind, seawater, and an implacable sun. The ground is red marl, as if kneaded with blood and the solar fire that still burns and scorches it more each day. The fig trees have withered branches and the gaunt look of people who have endured great hunger and find it hard to get by, leaning as if ready to flee, one foot already lifted. And yet, amid the overwhelming sadness, you will spot a drop of joy: caper bushes of extraordinary size that shelter a threshing-floor-sized clearing, and here and there a fringe of green reeds that, when the wind passes through them, sound like a flute. The buildings of the Colònia, scattered in a beautiful disorder along the bare, black beach full of pebbles—fired stones that have taken on such a furious red that it hurts to look at—contrast in a typical way with the white lime borders that frame the windows.” Here you can see many old photographs of the village

Colònia de Sant Pere, Artà, in the early 1970s. This is how Rafel Ginard saw it in his Croquis artanencs (1929): “… a wretched little place of tiny houses, fairground or nativity-scene huts, poor and miserable, with thin and meagre soil, where only tamarisks and a little vine manage to thrive, with scarcely any wealth beyond salty wind, seawater, and an implacable sun. The ground is red marl, as if kneaded with blood and the solar fire that still burns and scorches it more each day. The fig trees have withered branches and the gaunt look of people who have endured great hunger and find it hard to get by, leaning as if ready to flee, one foot already lifted. And yet, amid the overwhelming sadness, you will spot a drop of joy: caper bushes of extraordinary size that shelter a threshing-floor-sized clearing, and here and there a fringe of green reeds that, when the wind passes through them, sound like a flute. The buildings of the Colònia, scattered in a beautiful disorder along the bare, black beach full of pebbles—fired stones that have taken on such a furious red that it hurts to look at—contrast in a typical way with the white lime borders that frame the windows.” Here you can see many old photographs of the village

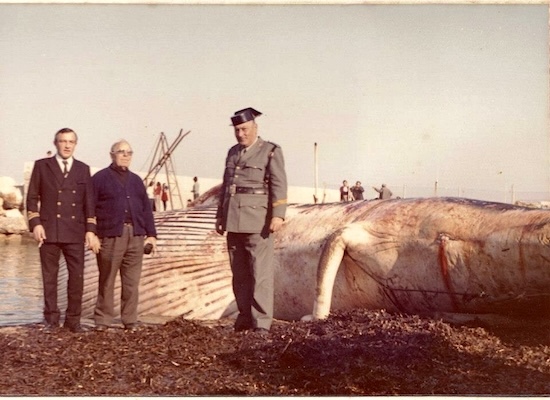

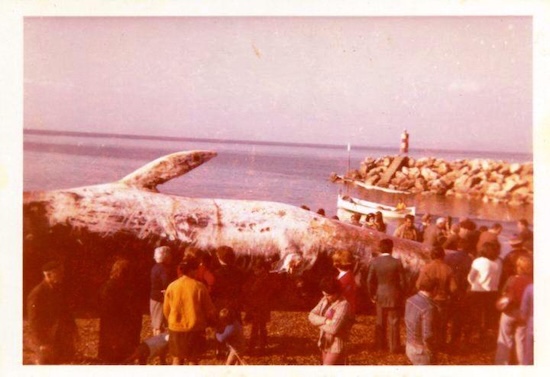

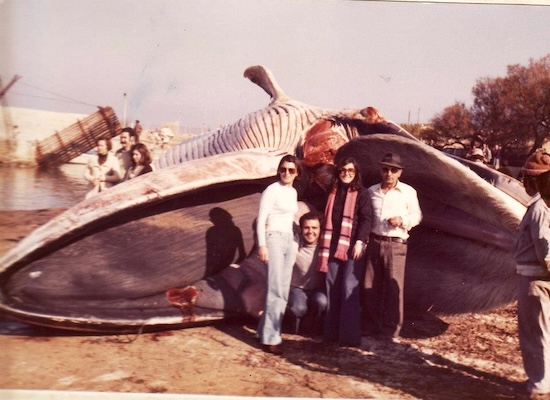

It is Friday, January 15, 1976. For less than two months now, Franco has been rotting in the Valley of the Fallen (in truth, he had already been doing so long before he was buried), and in Spain no one quite knows what is going to happen next. Dawn breaks over the Colònia de Sant Pere, a small fishing harbor in Mallorca, still untouched by tourist destruction, very close to Artà. The Guardia Civil colonel watches as, just a few meters from the harbor mouth, an intermittent spout appears in the water. Indeed, there is a whale circling there, edging ever closer to the moorings. It is enormous. And it seems badly wounded. By mid-morning, two fishing boats—far too fragile—nervously try to keep the animal from beaching itself inside the harbor, but they fail to move it. There is a lot of blood around. They decide that the best thing is to haul it out of the water, which they manage by tying ropes around its tail. The dying whale, exhausted, can only blow. It will remain alive and moan terribly when some boys from the Colònia, along with others who have run over from Artà to see the marvel, later climb on top of it. It is a carnival, the best possible prelude to the great night of Sant Antoni—of fire, the blessing of animals, and the devil; we are at the festive climax of winter, especially in Artà and the villages of the north of the island. By nightfall, the whale—a fin whale some 14 meters long—is dead, its full weight resting on the breakwater to which they have managed to drag it. And now we have all the ingredients for a film that could be told just as effectively in the neorealist, even sarcastic tones of Berlanga as with the metaphysical density of whale tales from Moby Dick—though the Mediterranean temperament strongly pushes toward the former.

The Guardia Civil and the Naval Command hurriedly trying to make clear their respective rights and authority over the monster’s corpse

The Guardia Civil and the Naval Command hurriedly trying to make clear their respective rights and authority over the monster’s corpse

Two days after the whale’s appearance, all the questions erupt. Whose is it? Who is responsible for this whole mess? What can the village gain from all this meat and fat—and from the bones? Could we hang the skeleton and make a museum to attract tourists? Where do we even begin? The whale starts to stink.

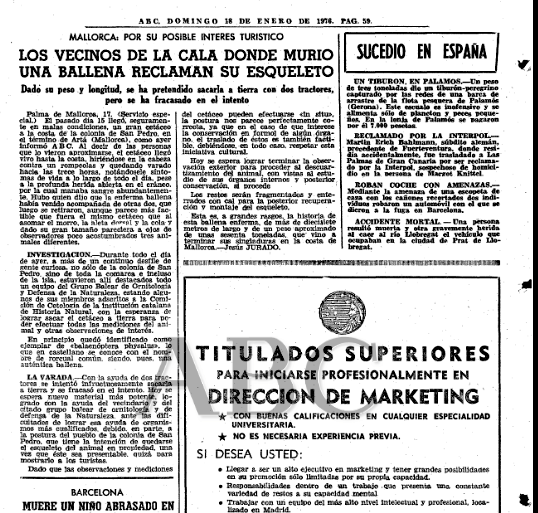

The morning after Sant Antoni, the news has already reached the national press. ABC reports on disputes over the “possible tourist interest” of displaying a whale skeleton in the village, against the desire of the Naval Command and the Oceanographic Institute to claim it, along with the minor intervention of some pioneering environmentalists from the GOB, who have their own ideas about preserving the remains. One can already sense a scenario of tons of meat, blood, and the onset of an unbearable stench

The morning after Sant Antoni, the news has already reached the national press. ABC reports on disputes over the “possible tourist interest” of displaying a whale skeleton in the village, against the desire of the Naval Command and the Oceanographic Institute to claim it, along with the minor intervention of some pioneering environmentalists from the GOB, who have their own ideas about preserving the remains. One can already sense a scenario of tons of meat, blood, and the onset of an unbearable stench

Fortunately, people in Mallorca tend to be peaceable by nature, and everything was gradually sorted out with goodwill and the beneficent touch of indolence that characterizes us. On other islands, a stranded whale has caused massacres, such as the one that broke out around 1833 at Convincing Ground, Australia. Our friend Miquel Àngel Llauger has just published his memories of those days that enlivened life in the Colònia de Sant Pere. He was thirteen at the time and was reading One Hundred Years of Solitude with fascination, so his account could only begin like this: “Many years later, facing the burnt white of the screen, the sixty-year-old writer recalls the distant dusk when his father took him to see the whale” (Díptic de la balena, 2025). It is a pity that no live report of the events was written and that no good photographs survive. Truth is thus relegated to individual memories and oral transmission among those who took part—and those who believe they did—with the inevitable discrepancies and heated arguments about who did what or decided otherwise. Even so, the photographs gathered in Fotos Antigues de Artà provide extraordinary testimony.

The first moments of the whale’s appearance, weakly splashing in bloodied water and banging against the rocks of the breakwater

The first moments of the whale’s appearance, weakly splashing in bloodied water and banging against the rocks of the breakwater

The first decision was to hook it to a boat and tow it back out to sea. The Oceanographic Institute warned that wind and waves would bring it back to the same spot, as indeed happened, despite tying two anchors to it in the hope it would sink. A week later it was back again, in far worse condition. The possibility—a classic one in such cases—of blowing it up with explosives was also considered, but discarded for lack of means.

The first decision was to hook it to a boat and tow it back out to sea. The Oceanographic Institute warned that wind and waves would bring it back to the same spot, as indeed happened, despite tying two anchors to it in the hope it would sink. A week later it was back again, in far worse condition. The possibility—a classic one in such cases—of blowing it up with explosives was also considered, but discarded for lack of means.

So the “final solution” was to fetch a powerful excavator (a local farmer’s tractor was not enough) and haul it ashore. A diver in a wetsuit went into the water to tie it by the tail.

So the “final solution” was to fetch a powerful excavator (a local farmer’s tractor was not enough) and haul it ashore. A diver in a wetsuit went into the water to tie it by the tail.

And then it was time to get serious. With chainsaws, the job turned into a real slaughter. Large chunks of meat were taken out to sea in the hope that such good food for the fish would benefit fishing. Some people took pieces home to put in their freezers. Others said the fat was as good as pork lard.

And then it was time to get serious. With chainsaws, the job turned into a real slaughter. Large chunks of meat were taken out to sea in the hope that such good food for the fish would benefit fishing. Some people took pieces home to put in their freezers. Others said the fat was as good as pork lard.

After many hours of almost futile work, when the stench had become so bad that one had to cover one’s nose with a handkerchief, they finally arrived at the solution to the final solution: dousing the large quantity of remains that could not be removed with jerrycans of gasoline and setting them on fire until they were reduced to ashes. It burned for a whole week.

After many hours of almost futile work, when the stench had become so bad that one had to cover one’s nose with a handkerchief, they finally arrived at the solution to the final solution: dousing the large quantity of remains that could not be removed with jerrycans of gasoline and setting them on fire until they were reduced to ashes. It burned for a whole week.

What was not properly calculated was that burning all that fat would produce black smoke and, worse still, sticky ashes that clung to walls, shutters, and windows—and even to clothes stored in wardrobes. For months afterward, every corner had to be scrubbed with detergent.

What was not properly calculated was that burning all that fat would produce black smoke and, worse still, sticky ashes that clung to walls, shutters, and windows—and even to clothes stored in wardrobes. For months afterward, every corner had to be scrubbed with detergent.

What ultimately became of those much-coveted bones remains a mystery. The Oceanographic Institute and the Naval Command quickly gave up any claim, probably so as not to have to assume any responsibility either. At first, the villagers celebrated the handover with enthusiasm, but in reality they were so fed up with the monster that they soon lost interest in the future of the remains and, once the festivities of Sant Antoni were over, returned to their own affairs. The stain of burned grease remained there for a long time as the sole testimony of the Leviathan’s visit. Miquel Àngel Llauger spent several months investigating what happened to the skeleton. He reports that some young people from the village collected the remains with the intention of cleaning them and putting them to some use, but that the pieces ended up being scattered. The great skull that could be seen for some years in a restaurant in Port de Pollença, the Restaurant Llenaire, has long since disappeared. It is known that one large bone was taken by the painter Miquel Barceló to his studio. Of the rest, nothing was ever heard again. The monster vanished, leaving only a black mark on the ground, just as demons disappear among the embers and sparks of the Sant Antoni foguerons. More slowly, and with his bones well accounted for, Franco was also disappearing during those same months.

Adrian Collaert, Piscium vivae icones (Antwerp: s.n., c. 1610)

Adrian Collaert, Piscium vivae icones (Antwerp: s.n., c. 1610)

Add comment