On October 18, 1944, the Red Army crossed the old German border. On October 21, they occupied the East Prussian village of Nemmersdorf (today Mayakovskoye, Kaliningrad region). When the Soviets were forced to withdraw briefly, German soldiers, doctors, and journalists arriving at the scene discovered the bodies of seventy-two brutally massacred German civilians and fifty French and Belgian prisoners of war who had been shot dead: women had been subjected to mass rape before being run through with bayonets, some were nailed alive to doors. The news, amplified by Nazi propaganda, spread rapidly, and the mass flight of the eastern German population toward the interior of the country began immediately.

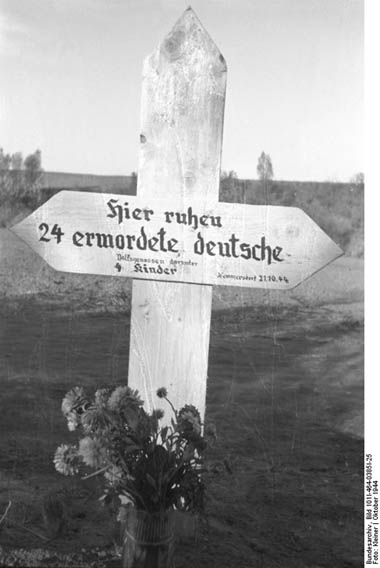

The memorial erected after the massacre in Nemmersdorf. When the Red Army returned, it destroyed this monument as well, just like all other German and non-German memorials and military graves

The memorial erected after the massacre in Nemmersdorf. When the Red Army returned, it destroyed this monument as well, just like all other German and non-German memorials and military graves

By the end of the war, around 7–8 million Germans had fled the eastern territories ahead of the Red Army. Those who managed to stay ahead of the Soviet advance found refuge in central Germany, in areas controlled by the Anglo-Saxons. Many, however, were slower—and most of them met the same fate as the people of Nemmersdorf. After the war, Soviet, Polish, Czechoslovak, and Hungarian authorities forcibly resettled roughly the same number of Germans once again into the new Germany.

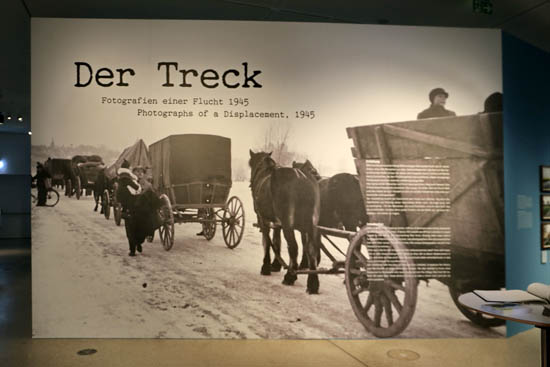

There is an abundance of memoirs and sociological studies about the integration of these refugees and their later lives, just as there is about the territories they left behind. But the flight itself is understandably far less well documented. This is precisely why the photo exhibition held this year at Berlin’s Deutschlandhaus—the documentation center of the Stiftung Flucht, Vertreibung und Versöhnung (Foundation for Flight, Expulsion, and Reconciliation), opened in 2021—is so important.

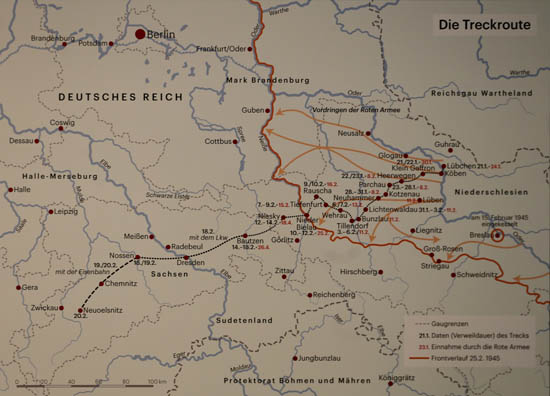

The photographs on display were taken by Hanns Tschira, who—after his Berlin apartment was bombed—fled with his family and his assistant, Marta Maria Schmackeitl, to war-protected Silesia, to the village of Lübchen an der Oder (today Lubów). They lived there for half a year, until the village itself was forced to flee on January 21, 1944. Tschira accompanied them on their five-week-long odyssey, documenting it in some 140 photographs.

The series was rediscovered by Lucia Brauburger while she was searching for images for a documentary film on modern German history, and was published in 2004, supplemented with notes by Tschira’s assistant, in the book Abschied von Lübchen: Bilder einer Flucht aus Schlesien. On this occasion, all 140 photographs are on display, along with a few additional ones showing the later fate of the refugees and the village. Unfortunately, the lighting of the exhibition is extremely unfavorable—if not downright amateurish: reflections abound, and this was impossible to avoid even in my own photographs of the display. To their credit, the images remain deeply moving nonetheless. In some cases, the reflection of the endless series of photos from the opposite wall even seems to add another layer of meaning.

Nazi authorities, who until the very last moment kept insisting on Germany’s imminent victory, paid no attention whatsoever to evacuating the civilian population. Everywhere, the affected villages were left to organize their own evacuation at the very last minute. In Lübchen, the district party secretary ordered the evacuation by telephone on the evening of January 20, 1945, when the Red Army was already just fifty kilometers from Lower Silesia. Men between the ages of 16 and 60 were required to report for service in the “people’s militia” (Volkssturm); only women, children, and the elderly were allowed to leave.

The gathering in the village began early in the morning of January 21. Tschira started photographing events from the very first moment.

Line-up of newly formed Volkssturm units in the district center of Guhrau, followed by their departure eastward to repel the advancing Red Army

Line-up of newly formed Volkssturm units in the district center of Guhrau, followed by their departure eastward to repel the advancing Red Army

Gathering in Lübchen. Final photographs in front of family homes. Here Tschira photographs his own family and their hosts. At the time, it was believed they would only move to the nearby district center of Lüben (today Lubin) and return soon. No one yet imagined that this morning would be the last time they would ever see the village. In the image below, his 15-month-old daughter Gisela sits in a basket; she would not survive the journey.

Gathering in Lübchen. Final photographs in front of family homes. Here Tschira photographs his own family and their hosts. At the time, it was believed they would only move to the nearby district center of Lüben (today Lubin) and return soon. No one yet imagined that this morning would be the last time they would ever see the village. In the image below, his 15-month-old daughter Gisela sits in a basket; she would not survive the journey.

The gathering took place in the village center, in front of Fritz Hanke’s general store (above) and Bruno Peickert’s butcher shop (below). A total of 350 people gathered from Lübchen and the neighboring village of Korangelwitz, including 120 children. They were allowed to take only the bare essentials. Since the village lay along the Oder and had few proper roads, transport relied mainly on boats, and only twelve carts could be assembled. Some of the horses had never pulled a cart before. With the men absent, the women had to bear most of the burden. The temperature was minus 15°C, and snowstorms soon followed. From the Guhrau district alone, sixty such columns set out in those days, involving around 25,000 people.

The gathering took place in the village center, in front of Fritz Hanke’s general store (above) and Bruno Peickert’s butcher shop (below). A total of 350 people gathered from Lübchen and the neighboring village of Korangelwitz, including 120 children. They were allowed to take only the bare essentials. Since the village lay along the Oder and had few proper roads, transport relied mainly on boats, and only twelve carts could be assembled. Some of the horses had never pulled a cart before. With the men absent, the women had to bear most of the burden. The temperature was minus 15°C, and snowstorms soon followed. From the Guhrau district alone, sixty such columns set out in those days, involving around 25,000 people.

Most of the dramatic photographs capture the long trek itself: marching on in cold, snow, and rain, sometimes stopping briefly, sometimes for a few days where they were taken in, then moving on again. Exactly one month and 350 kilometers— and even then they were luckier than the refugees from East Prussia.

The column leaves the village.

The column leaves the village.

With carts in short supply, many—especially the boatmen—travel by bicycle, while mothers with small children push them in prams for the entire 350 kilometers.

With carts in short supply, many—especially the boatmen—travel by bicycle, while mothers with small children push them in prams for the entire 350 kilometers.

Many of the images are about solidarity: villagers and fellow refugees sticking together, helping one another. And about the help they receive—food, shelter, medical care, a ladle of hot soup, even a cup of coffee for everyone—in the Silesian villages they pass through, villages that themselves are evacuated just a few days later. Judging by the memoirs, they received far more support here than at their final destinations in central Germany, where they were often still being called “Poles” or “Gypsies” decades later, and locals forbade their children from playing with the newcomers’ kids.

In Lichtenwaldau, everyone receives a cup of coffee—an extremely rare treasure in wartime. Two days later, this village is evacuated as well.

In Lichtenwaldau, everyone receives a cup of coffee—an extremely rare treasure in wartime. Two days later, this village is evacuated as well.

In Nieder Bielaubau, on the banks of the Neisse, the Wehrmacht’s last field kitchen cooks for the refugees before they all move on again.

In Nieder Bielaubau, on the banks of the Neisse, the Wehrmacht’s last field kitchen cooks for the refugees before they all move on again.

At the same time, the images do not show some features described by memoirs: devastation, dead horses and human bodies lying by the roadside, countless children’s graves, the Wehrmacht’s chaotic retreat, collapsing elderly people, sick children, and mothers’ desperation.

Tschira was a professional photographer. He was not merely documenting events; he was almost certainly already thinking about how the images might be used, selecting what he saw with a future audience—and its tastes—in mind. After the war, some of his photographs were indeed published in various places, not as images of the specific Lübchen column, but as general illustrations of the eastern flight.

Frankfurter Illustrierte, 1954

Frankfurter Illustrierte, 1954

The survivors from Lübchen reached Bautzen on February 20, where they once again encountered functioning structures. From there, they were transported further by truck: some to the Ore Mountains, others to what would later become West Germany. Most of them never saw the village of Lübchen again, which they had been forced to leave so suddenly and without farewell on the morning of January 21, 1944.

Lübchen became Lubów for the Poles, in Silesia, which was handed over as compensation for eastern Poland. Refugees arrived here as well: partly Poles from Soviet-occupied eastern Poland, partly Ukrainians from Poland who were resettled by the Polish government during Operation Vistula in 1948 because of their alleged support for Ukrainian partisan fighters against communism. Among both groups were people who understood the pain of displacement. This is how, in the decades after the war, some returning German families formed friendships with the Polish and Ukrainian families living in their former homes—friendships that, in some cases, have endured across generations to this day.

Polish school in Lubów, with a Ukrainian teacher resettled from the Vistula region

Polish school in Lubów, with a Ukrainian teacher resettled from the Vistula region

Adam Strombek (1935–2013), whose family was murdered by Ukrainian Nazis in Nowa Brykula (today Нова Брикуля, Ternopil district, Ukraine). In Lubów, they were given the house of the baker Beschorner, and Strombek later became a levee guard on the Oder.

Adam Strombek (1935–2013), whose family was murdered by Ukrainian Nazis in Nowa Brykula (today Нова Брикуля, Ternopil district, Ukraine). In Lubów, they were given the house of the baker Beschorner, and Strombek later became a levee guard on the Oder.

Members of the Strombek and Beschorner families in Lubów, during visits by the latter beginning in 1975.

Members of the Strombek and Beschorner families in Lubów, during visits by the latter beginning in 1975.

Hanns Tschira’s camera and two period children’s toys on display: most likely the same two dogs seen in his children’s hands on the cover of a Hungarian magazine

Hanns Tschira’s camera and two period children’s toys on display: most likely the same two dogs seen in his children’s hands on the cover of a Hungarian magazine

Add comment