Every cemetery is a local history museum. Their successive tombs document the social history of the place. Military cemeteries, however, are documents of grand history: colored pins on a general’s map, connected with others by arrows, leading finally to the massive black mass grave of the ultimate victory. A military cemetery is created after a single battle and never expands. Those resting here do not represent families or social or ethnic groups—they embody the broader context of that war.

We’ve written about military cemeteries many times: Austro-Hungarian military cemeteries in the Carpathians, Jewish military cemeteries in Galicia, two Hungarian military graves on the Russian front, two Russian military cemeteries on the Hungarian front, the Hungarian military cemetery destroyed by the Russians and still surviving two Hungarian military graves on the Russian-Hungarian front, and the German soldiers’ cemetery destroyed by the Russians at Georgia’s Cross Pass. And there are many more stories waiting to be told.

Today I want to write about two World War I Hungarian prisoner-of-war monuments, recommended to me by my restorer friend Károly Payer, who restored them on behalf of the Hungarian Museum of Military History.

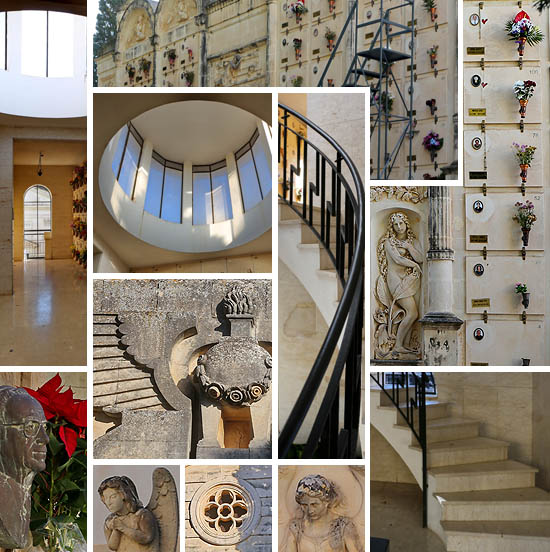

The cemetery in Vittoria, southern Sicily, doesn’t feel like a Central European cemetery. It’s more like a small town, with crypts and columbaria lining the streets by the way of houses.

Among the buildings, the small, square-plan white marble crypt does not stand out; its façade, supported by two columns, is decorated with a large Hungarian coat of arms and inscriptions in Italian and Latin:

|

Ai soldati ungheresi defunti in Italia |

To the Hungarian soldiers who died in Italy |

In Vittoria, at the end of 1915, after the first major battles on the Isonzo front, a POW camp was established—the furthest from the front. Hungarian prisoners, totaling 18,000 over the course of the war, were sent here. The 12,000-person camp was almost half the town’s population. Locals welcomed the Hungarians warmly, perhaps remembering Garibaldi’s times. Prisoners could work in the fields or on roads, receiving the same pay as locals. They were allowed out twice a week and could interact with the townsfolk; some stayed on after the war.

Thanks to this good treatment, mortality was low. However, in 1918 the Spanish flu struck indiscriminately, claiming 118 Hungarians. They were buried in a mass grave in the cemetery. In 1924, the former camp commander Giovan Battista Parrini proposed building a memorial chapel over the grave. A committee was formed, and by 1927 the chapel was completed. Its architect, Árpád Kirner, has his name inscribed on the gatepost.

After World War II, the chapel was neglected by Hungary. It was only renovated in 2017, on the 90th anniversary of its construction, by the Hungarian Military History Institute and Vittoria’s Hungarian twin town, Mátészalka. The chapel originally had stained-glass windows designed by the renowned Miksa Róth, which disappeared at some point. The original drawings survive at the Miksa Róth Museum in Budapest, but they were not used to recreate the windows.

Giancarlo Francione and Dezső Juhász wrote a bilingual Hungarian-English book in 2017 about the POW camp and chapel, titled Hungarian Chapel in Sicily.

The Botkino Cemetery in Tashkent lies well outside the old city. No surprise: during World War I, POWs sent to eastern Russia were settled far from city centers. Here, next to the former Russian village of Botkino, Tashkent’s first non-Muslim cemetery had been established, mainly with Russian and Ukrainian Orthodox graves, but also Armenian and Jewish sections. Hungarian prisoners who died in the nearby camp hospital were buried here too, regardless of religion.

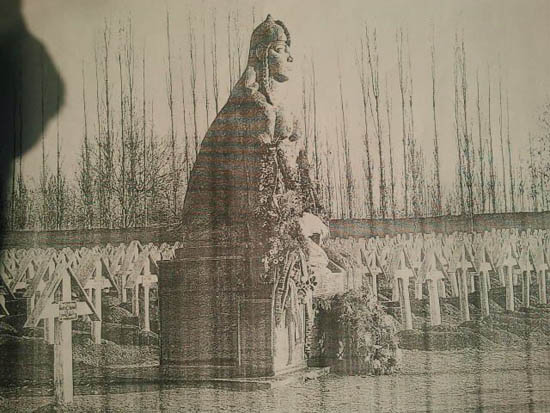

The prisoner cemetery, as seen in a period photograph, originally consisted of simple wooden crosses. After the war, however, the Hungarian officers—who received pay even in captivity, allowing them to go home before the privates—pooled their money so that the sculptor István Lipót Gách, also imprisoned with them, could create a more lasting memorial for the deceased.

By that time, István Gách was already a renowned sculptor. Born in 1880, he trained in György Zala’s workshop and contributed to the Budapest Andrássy Memorial and the Millennium Monument—the latter including his relief of Saint Stephen receiving the crown from the Pope. After several winning but unrealized memorial competitions, he went to Paris, and upon returning home, primarily created tombs for Budapest’s elite families, including the Gundel, Löw, and Reviczky families. During his Tashkent captivity, in addition to the Hungarian memorial, he also made thirty-two (!) sculptures for the local neo-Gothic Polish Catholic cathedral built between 1912–1925. Sadly, these disappeared during Soviet times, when the church was left ransacked.

Károly Payer sent me approximate coordinates of the memorial, but it’s still not easy to find. The wooden crosses were long gone, replaced by humble Russian graves, concrete tombstones, welded iron Orthodox crosses, and garish artificial flower wreaths tied with wire.

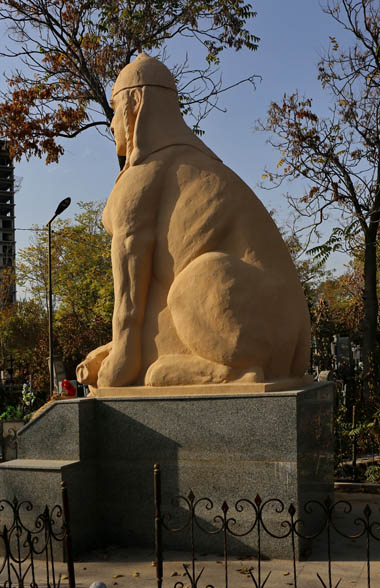

Making my way through the maze of plots toward the edge of the huge cemetery—which on the map isn’t even marked as part of the cemetery anymore, and beyond whose walls the Khrushchyovkas of Tashkent’s suburbs rise—I suddenly spot the surreal creature poking its sand-yellow head out from the vegetation covering the graves.

The memorial is a massive crowned sphinx, with large breasts, a powerful rear, ancient Hungarian braids, and a cap, gazing off into the distance with blind eyes. The symbolism isn’t entirely clear: does it hint at the mystery of life and death, or perhaps allude to the eastern origins of the Hungarians buried here?

At the sphinx’s feet, a half-naked—but cap-wearing according to regulations—soldier bends over the ground, mourning his comrades. In front of him lies a carved grave wreath, containing some dried flowers and a fresh bouquet of red flowers I brought to the grave in memory of my grandfather, who was a POW in Siberia during World War I.

The gravestone bears inscriptions in Hungarian and Russian: MAGYAR TISZTEK AZ ELHUNYT MAGYAR KATONÁKNAK (Hungarian officers to the deceased Hungarian soldiers) – ВЕНГЕРСКИЕ ОФИЦЕРЪ ВЕНГЕРСКИМЪ СОЛДАТАМЪ. In the obviously new inscription, written in old orthography—probably copied from an earlier plaque—the final hard sign in ОФИЦЕРЪ would ideally be Ы to indicate the plural “officers.” Beneath the marble plaque lies the original broken clay tablet: BAJTÁRSAK BAJTÁRSAKNAK (Comrades to comrades).

We know relatively little about the further fate of the Hungarian POWs in Tashkent. After the 1918 Brest-Litovsk peace treaty, many returned home—but with the Russian Civil War and the anti-Hungarian Czech Legion blocking the road, heading west was hardly straightforward: most circumnavigated half the globe, like Károly in our earlier series Pink Letters, who likely returned via Japan to Kis-Korona Street in Óbuda.

Many stayed: of the two million Austro-Hungarian POWs, about fifteen thousand. Some quotes on this from Béla Fábián’s 6 Horses – 40 Men. POW Notes (1930):

“In the city, one stumbled across Hungarian everywhere. More Hungarian was spoken here than in the main square of some small town in the Great Plain.”

“Days passed, and the mood gradually calmed; no news of Siberia or evacuation, only the soldiers died on quietly. Hardly anyone remained from the Przemyśl men. It was clear that the enlisted camps would die out to the last man. The sad funeral processions of the privates, some shabby men trailing behind the coffins-laden wagons, had become so familiar a sight in the city that it was rare not to see such a procession daily.”

“Those who turned Red got boots. Those who didn’t got typhus. It wasn’t an ideological question.”

As the last quote suggests, many Hungarians stayed by entering the service of the new authorities. This became the “Tashkent school.” From their ranks came many later cadres, political commissars, and members of execution squads. This story remains a blind spot in Hungarian history. After the war, it was awkward to talk about, and not many witnesses survived: either they assimilated, or were killed as foreigners during the Great Terror.

István Lipót Gách made it home. Between the two world wars, he mostly created tombs and war memorials at home. His best-known work is the World War I memorial of the 3rd Szeged Hussar Regiment (1943) at Magyar Ede Square in front of the Art Nouveau Reök Palace in Szeged. Like the Tashkent sphinx, it’s also “rear-heavy”: the building behind it, Szeged’s Faculty of Law and State Sciences, is commonly referred to as “behind the horse’s rear” because of it.

Add comment