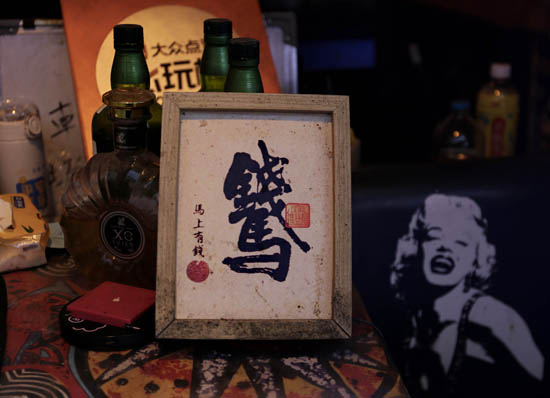

I am pondering this character, spotted in the window of a music bar on the tourist street in Yangshuo. It’s very complex: at the bottom is the character for horse, at the top the character for money, and it’s obvious that it was calligraphed here precisely because of this complexity, much like the big character for biang noodles.

In principle, a compound Chinese character should consist of a radical, which shows the semantic category it belongs to—here it would be 馬 mă, so the word somehow relates to horses, galloping, or speed—and a phonetic, which shows how the word is pronounced, or at least how it was pronounced in the Qin dynasty, 3rd century BCE, when the first Chinese character dictionaries were compiled. Here, that would be 錢 qián, meaning money. But dictionaries don’t recognize such a compound character.

Then I start reading the small text on the left and slap my forehead: it’s a word puzzle! The text 馬上有錢 (mă shàng yŏu qián) literally means: “money on horseback,” i.e., “may money arrive at your house immediately / be instantly rich”! (馬上 mă shàng, “on horseback,” also means “immediately.”) And indeed, in the fictional character, the money is on the back of the horse.

It’s a beautiful example of how Chinese writing has retained its pictorial nature: Chinese readers still see the original image behind every character, and in calligraphy, a character can unexpectedly revert to a picture.

You might think that in the nightlife of Yangshuo, they’re offering quick loans or cash withdrawals to tourists left without money. But no. Traditionally, this is the formula for New Year greeting cards – especially in 2026, the Year of the Horse. Or for New Year lucky coins, where, as our pig motif, a horse appears carrying the money itself, fully turning the good wishes expressed in the characters back into an image.

Add comment