Anatolian Archaeology recently reported on a curious Hittite object that has just come to light in Eskiyapar. The piece is a one-handled clay cup from the 17th–16th centuries BC, that is, from the earliest phase of the Hittite Empire. What makes it special is that someone is sitting inside the cup: a naked female figure with huge eyes and a sun-disk-like crown of hair edged with eight roundels. She presses both hands to her breasts, as if trying to squeeze milk from them — a gesture symbolizing abundance and fertility, common in Hittite and earlier Anatolian iconography. In front of her, on the bottom of the cup, stands a small round table with flatbread on it, and beside it a jug with an animal head.

The Eskiyapar cup. My own photo from the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations in Ankara

The Eskiyapar cup. My own photo from the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations in Ankara

If this were contemporary ceramics, we’d call it a cute gimmick. But gimmicks weren’t really the Hittites’ thing.

Although Hittite culture was only identified about a century ago, and its writing fully deciphered barely fifty years ago, an impressive body of texts and archaeological parallels has already accumulated — enough to allow a surprisingly detailed reconstruction of the object’s function and meanings.

The closest parallels to the female figure seated in the cup are small female statues whose enormous hair-crown — and sometimes the entire figure — is made of solid gold. This is Arinnitti, “the Sun Goddess of Arinna,” as the Hittite sources call her.

The gold statue of Arinnitti from the MET Museum of Art. Several similar figurines are also preserved in museums in Turkey

The gold statue of Arinnitti from the MET Museum of Art. Several similar figurines are also preserved in museums in Turkey

The temple city of Arinna lay near the Hittite capital, Hattuša. Here stood the sanctuary of the Sun Goddess, for the Hittites revered the life-giving Sun in female form. Her husband was Tarhunna, the Storm God, and together they were the chief deities of the Hittite pantheon, to whom the Hittite ruler and his wife regularly offered sacrifices.

On the rock relief at Fıraktın in Cappadocia, about 50 km south of Kayseri, King Hattusili III (c. 1275–1245 BC) offers a sacrifice to Tarhunna, while his wife Puduhepa presents an offering to Arinnitti. In front of each stands a round little table like the one before the goddess in the cup — bread on Tarhunna’s, and a bird-headed vessel on Puduhepa’s. And each pours liquid from a beaked vessel into a bowl placed on the ground or on the table, just like the one standing before the goddess inside the cup.

Ian Rutherford writes in his excellent Hittite texts and Greek religion (2020), in which he explores Anatolian elements in Greek religion:

If a Greek of the 1st millennium had witnessed Hittite offerings, one thing s/he could not have failed to notice is the strong focus on bread. Hittite Anatolia was in some sense a ‘bread culture’. We saw, how local sacred calendars tend to be constructed round ḫarsi-grain, which is stored through the winter and turned into loaves of bread in the spring. In Greek sacrificial ritual, we do not normally think of bread as being so important, although there are occasional references to artos, pelanos, and pemmata in Greek sacred laws. And there are also some precise parallels; e.g. in both cultures loaves can be made in the form of bovines.

The symbolic value of libation in Hittite ideology is well illustrated in the Fıraktın relief where Hattusili III and Puduhepa are represented pouring libations to Tessub and Hepat [the Hatti names of the two gods]. Indirect evidence is provided by so-called ‘cup marks’ cut into bedrock, which are found at various sites in the 2nd millennium BC, including Kaymakçı in Western Anatolia. Libations were commonly of wine or beer or both, sweet milk, oil and honey; the unidentified liquids tawal and walḫi are frequently mentioned as well; occasionally we find blood or fat; libation of water is rare.

Libation usually takes place in the context of a longer ritual programme. Sometimes the person performing the ritual is said to speak during or after the libation, as at the spring festival of the Storm God of the Rain at Hakmis, where the participants are said to pour a bowl of beer on the ground and make a short prayer for the rain: ‘O Storm God, my lord, make the rain plentiful! And make the dark earth satiated! And, O Storm God, let the loaves of bread be plentiful!’ This parallels the association between libation and invocation or prayer in Greek ritual. Libation can take place at the crossroads, as in Greece, or front of the altar. On the third day of the Royal Funerary Ritual, the embers of the funeral pyre are extinguished by ten vessels of beer, ten vessels of wine, and ten vessels of ‘walḫi’, surely a form of libation, as in the Iliad the Myrmidons extinguish the embers of Patroclus’ funeral pyre with wine.

The central role of libation is also emphasized by the texts analyzed by Volkert Haas in his collection Geschichte der hethitischen Religion (1994). A recurring motif in these, however, is that the ruler not only offers a drink-offering to the god but afterwards also “drinks the god” himself:

“After this the king, standing, drinks the Sun Goddess of Arinna and all the Mother Goddesses of Arinna; he plays the great lyre and breaks the bread.”

Scholarship long struggled to make sense of the formula “to drink the gods.” According to the first analyses, the newly discovered cup may help explain it. After the king has given drink to the goddess, he fills the cup with a sacred beverage and drinks from it himself, as if drinking the liquid that springs from the breast of the all-nourishing Sun Goddess — thereby symbolizing the reciprocity of contact established through the liquid. The movement of the fluid is a performative event: in fact, they are not “drinking the god,” but dramatizing their relationship with the deity through the liquid.

Haas identifies the cult city of Arinna precisely with Eskiyapar, where the cup was found. And he sets the number of the “Mother Goddesses” — perhaps female ancestors of the dynasty, which may explain why the queen often makes offerings to them — at eight, exactly the number of roundels we see in the hair of the goddess seated in the cup.

What is especially fascinating about the cup is not only that the symbolic source of the drink, the Sun Goddess herself, sits within it, but that the entire vessel is arranged like a complete sanctuary: alongside the cult statue of the Sun Goddess stands a small circular altar similar to the one on the Fıraktın relief, bearing broken flatbread, and a bird-headed jug of the sort used to pour the libation.

In this sense the cup is a micro-sanctuary — a portable object that

• manifests divine presence — an epiphany

• structures ritual action

• models sacred space

• creates a choreographed viewpoint (holding the handle in the right hand while drinking, one faces the goddess directly)

• and through ritual use temporarily becomes sacred space.

Hittite religion was decentralized, with many local cults. Perhaps this is why they possessed several cultic objects that functioned as “mobile sanctuaries,” allowing rituals to be performed outside the great temples — at home or on the road.

In a certain sense, libation vessels themselves — the rhyta — functioned this way. These were always shaped like animal heads, as if the sacred liquid itself flowed from a deity embodied in animal form, meaning that the person making the offering communicated with the intended recipient through that divine intermediary.

The “twin-bull rhyton” in the Sivas Archaeological Museum depicts the two bulls of the god Tarhunna, Sherri and Khurri

The “twin-bull rhyton” in the Sivas Archaeological Museum depicts the two bulls of the god Tarhunna, Sherri and Khurri

Animal-shaped libation vessels from the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations

Animal-shaped libation vessels from the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations

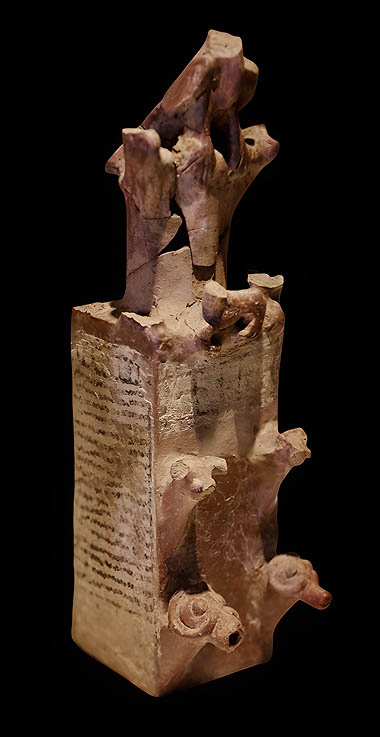

Some Hittite libation vessels, however, depict not just a single animal-headed deity but an entire sanctuary, which is activated through the pouring of liquid. One such example is the Inandık vase from around 1600 BC, which shows a complete sacrificial ceremony — with procession, musicians, sacred architectural space, and the sacrificial altar — almost like a visual script for the ritual itself. Around the rim of the vase are four bull-headed spouts, and the liquid can be poured into the vessel’s double body so that it flows out through the bulls’ heads, as if from four rhyta at once. In this way, performing the libation ritual seems to set an entire sanctuary in motion. Inandık-type cult vases are not merely carriers of ritual scenes but portable, performative ritual spaces in which temple events are miniaturized both iconographically and functionally.

The Inandık “A” vase in the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations in Ankara, my own photographs

The Inandık “A” vase in the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations in Ankara, my own photographs

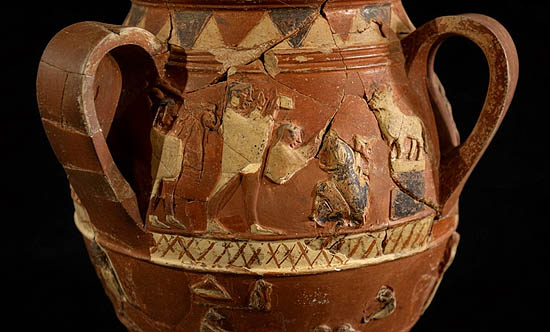

A similar ritual vessel comes from Çorum, also preserved in the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations.

Sanctuary-shaped libation vessel in the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations

Sanctuary-shaped libation vessel in the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations

Small sanctuary models have also survived. We do not know exactly how they were used, but they probably served as substitutes for real sanctuaries during ritual performances.

Sanctuary model with a goddess from Eskiyapar, Museum of Anatolian Civilizations

Sanctuary model with a goddess from Eskiyapar, Museum of Anatolian Civilizations

The essence of these micro-sanctuaries is that the vessel itself already contained the ritual action in some form — as a symbolic setting or as a kind of script — so that the ritual effectively took place “within” the object itself.

We do not know who used these micro-sanctuaries or exactly how — whether within real temples or as substitutes for them in private homes. What is certain is that they were important ritual tools within Hittite religion, whose most essential elements, judging from the large number of surviving religious texts, were precisely these ceremonial practices.

Çağatay Akyol: Hittite suite. „The king … plays the great lyre…”

Add comment