“As the priest raised the Host high, the signal was given, and Bernardo Bandini, Francesco Pazzi, and the other conspirators formed a circle and closed in on Giuliano. Bandini was the first to plunge his sword into the young man’s chest, running him through. Mortally wounded, he staggered a few steps, trying to flee, but the others pursued him. His breath failing, he collapsed to the ground. As he lay there, Francesco stabbed him again and again with a dagger. Thus perished a young man loved by all.”

Angelo Poliziano: Pactianae coniurationis commentarium

(Notes on the Pazzi Conspiracy), 1478

On April 26, 1478, during the High Mass on the fifth Sunday after Easter in Florence Cathedral, a group of conspirators gathered from the city and beyond murdered Giuliano de’ Medici and attempted to kill his brother Lorenzo as well. Lorenzo, though wounded, kept his presence of mind and defended himself with his sword until his friends dragged him into the sacristy and barred the heavy bronze door behind them.

Botticelli: Giuliano de’ Medici, 1478. Berlin, Gemäldegalerie. The closed eyes indicate that the portrait was painted after Giuliano’s death

Botticelli: Giuliano de’ Medici, 1478. Berlin, Gemäldegalerie. The closed eyes indicate that the portrait was painted after Giuliano’s death

Meanwhile, another armed group of conspirators, led by Francesco Salviati, Archbishop of Pisa, hurried to the Florentine town hall to seize control of the city. Cesare Petrucci, the city captain, noticed the archbishop’s agitation, had the doors of the palace shut behind him, and rushed with members of the Council of Eight to the tower, where they rang the city’s alarm bell.

Armed supporters of the Medici poured into Piazza della Signoria. Once the gates of the town hall were opened, the lesser culprits were simply torn to pieces—some fragments, a head and a shoulder, were carried off as trophies to the gates of the Medici Palace—while the more prominent figures, including Archbishop Salviati, were hanged from the windows of the town hall, ropes around their necks. According to Angelo Poliziano, who had witnessed the events in the cathedral with his own eyes but reached the Signoria only at this stage, Salviati, in a final effort, even tried to bite into the body of Francesco de’ Pazzi hanging beside him—the very man who had drawn him into the conspiracy.

After the attack, Lorenzo de’ Medici had numerous busts of himself made and displayed throughout the city to show that he was alive. This sculpture was acquired by the Berlin Skulpturensammlung in 1839

After the attack, Lorenzo de’ Medici had numerous busts of himself made and displayed throughout the city to show that he was alive. This sculpture was acquired by the Berlin Skulpturensammlung in 1839

I was present at the hanging myself. I can still see it as if it were today: the square in front of the town hall was swarming with armed men. The grim stagehands were just looping the ropes around the victims’ necks—and under their cloaks, around their waists, to hold them as they were suspended from the windows. On the wooden-and-plaster replica of the Loggia dei Lanzi, the images of the hanged men were already painted. Botticelli would paint them much later, after the bodies had been removed, as a warning to the people—but here they were already visible before the execution, so the entire episode could be shot in a single day for the second season of The Medici. So it happened, word for word as I tell it, in the town square of Volterra, because only there did an authentic architectural backdrop survive, Florence’s Piazza della Signoria having been rebuilt in an eclectic style in the 1860s.

An exhibition titled The Pazzi Conspiracy has just opened at Berlin’s Bode Museum. It is not easy to find, as it is tucked away in the coin cabinet on the second floor. This is no coincidence: at the heart of the exhibition stands a medal commissioned by Lorenzo de’ Medici in the autumn of the very same year, to commemorate the crushed conspiracy. Around this centerpiece, the museum has assembled further Medici medals and Medici portraits from its own collection.

To understand the meaning and significance of this medal, we first need to understand

• what role medals played in Renaissance Italy,

• what caused the Pazzi Conspiracy,

• what its consequences were,

• and, based on all this, whom Lorenzo wished to address—and what he wished to say—with this medal.

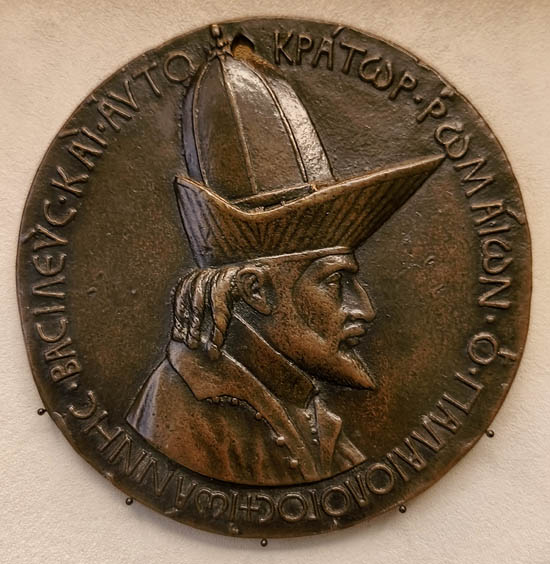

The medal—not as a coin, but as an entirely independent artistic genre—became popular in Italy around the middle of the fifteenth century, and from there spread across Europe. Its very first example is the portrait medal made by Pisanello in 1438 of the Byzantine emperor John VIII Palaiologos, who had come to Italy for the Council of Ferrara–Florence; this medal is on display in the room next to the Pazzi exhibition.

On the obverse, the Byzantine emperor appears in profile—in the conventional pose of ancient imperial coinage—drawn from life by Pisanello, who was present at the council, and surrounded by his imperial title in Greek. On the reverse, we see the same ruler on horseback, praying before a cross, with a mounted page turning his back to us behind him, and the inscription “the work of Pisano the portrait painter,” again in Greek.

What was the purpose of this medal? Scholars generally agree that the organizers of the council—Cosimo de’ Medici, or perhaps Leonello d’Este—commissioned it from Pisanello in order to distribute it among the distinguished Western participants. Its aim was to translate the exotic Eastern ruler, arriving with an equally exotic entourage, into a Western visual language as a living, authentic “Roman emperor”. In doing so, it underlined his legitimacy at the council convened to unite the Eastern and Western Churches, while at the same time enhancing the prestige of Cosimo de’ Medici, who organized and financed the event.

All this already sums up the essential features of the new genre, the medal—the medaglia:

• it is not a coin, but a much larger work of art (this one measures 103 mm in diameter),

• it bears an individual portrait of a contemporary figure,

• it serves representational and political purposes,

• and it conveys a message tailored to a specific occasion.

According to John Graham Pollard’s Renaissance Medals (2007), the standard monograph on the subject, this very piece marks the birth of the Renaissance medaglia as an autonomous medium of representation.

The intended recipients of a medaglia were members of the elite. It circulated selectively—through courtly gift-giving and diplomatic channels—allowing its commissioner to decide which decision-makers to influence. Proper interpretation required the emerging humanist milieu of the time. As Pollard puts it, its function was one of political self-fashioning: the patron articulated his own political identity, moral qualities, historical role, and the necessity of that role in response to a specific event—while simultaneously interpreting the event itself. The message of the medal was conveyed by diplomats, explained by humanists, and decoded within courtly circles; in this way, self-fashioning evolved from an individual gesture into a collective discourse.

How did Lorenzo de’ Medici’s Pazzi Conspiracy medal meet these criteria?

To answer this, we must first see what led to the Pazzi Conspiracy and what grave challenges Lorenzo had to face after the conspiracy had been crushed.

The Pazzi Conspiracy was, in fact, misleadingly named after the Pazzi family—almost euphemistically—in order to avoid pronouncing the name of its true driving force: Pope Sixtus IV.

The conspiracy was embedded in the context of Italian great-power politics and sought to overturn the framework established by the Peace of Lodi in 1454.

Italy after the Peace of Lodi (1454)

Italy after the Peace of Lodi (1454)

By the mid-sixteenth century, five great powers had emerged in Italy: the Duchy of Milan, the Republics of Venice and Florence, the Kingdom of Naples, and the Patrimonium Petri, the Papal States. Their borders had taken shape over the preceding centuries through successive wars of expansion and defense, and in the wake of the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople in 1453 they agreed in Lodi in 1454 to cease fighting one another and instead unite their forces against Ottoman expansion.

Yet the expansionist instincts of great powers are not easily switched off overnight. The five Italian states, well acquainted with one another, entered into secondary security alliances: the trio of Milan, Venice, and Florence stood opposed to the alliance of the Papal States and Naples, while all sides kept a vigilant eye on one another, watching to see who would be the first to overstep the boundaries assigned to them.

It was the Papal States that, in 1471, came under the rule of Sixtus IV of the Rovere family. Today he is remembered as a great builder, the founder of the world-famous Sistine Chapel—something that, as will soon become clear, we owe to his mortal enemy, Lorenzo de’ Medici. In his own age, however, Sixtus was more closely associated with the establishment of the Spanish Inquisition (1478), the legitimation of Black slavery (1481), and above all with nepotism on an industrial scale. He elevated countless nephews—and perhaps even one or two illegitimate sons—into cardinalatial and secular positions, entrusting them with the governance and expansion of the Papal States.

Melozzo da Forlì: Sixtus IV appoints Platina prefect of the Vatican Library, c. 1477. The figures depicted are all nephews of the pope: from left to right Giovanni della Rovere, Girolamo Riario, Bartolomeo Platina, Giuliano della Rovere (the future Pope Julius II), and Raffaele Riario—several of whom would later play roles in the conspiracy

Melozzo da Forlì: Sixtus IV appoints Platina prefect of the Vatican Library, c. 1477. The figures depicted are all nephews of the pope: from left to right Giovanni della Rovere, Girolamo Riario, Bartolomeo Platina, Giuliano della Rovere (the future Pope Julius II), and Raffaele Riario—several of whom would later play roles in the conspiracy

Sixtus IV came from a poor family and rose from a poor order—that of the Franciscans—so it is hardly surprising that, once he attained papal power, he threw himself with bottomless appetite into the world of the wealthy. Disregarding established conventions and unspoken rules, he strode into his neighbors’ territories like a Renaissance-era Trump, and his closest neighbor was Florence. In defiance of custom, and without consulting Florence, he appointed two nephews to the archiepiscopal sees of Pisa and Florence: Francesco Salviati and the feeble-minded Pietro Riario. The latter was notorious in Florence for the habit of presenting each new lover with a golden chamber pot—a practice that became proverbial until his disillusioned Creator removed him from earthly circulation at the age of twenty-eight. Another nephew, Giovanni della Rovere, he married to the daughter of Federigo da Montefeltro, the invincible lord of Urbino, elevating Federigo to the rank of duke and—contrary to his previous allegiance—turning him into an enemy of Florence. The true breaking point with Florence, however, came when Sixtus purchased the city of Imola from the Duke of Milan for 40,000 gold ducats, intending to bestow it upon yet another nephew—or perhaps son—Girolamo Riario, thereby initiating the expansion of the Papal States into Romagna. To make matters worse, he sought to borrow the purchase price from the Medici bank. Lorenzo de’ Medici, deeply affected by this prospective change of rule—since Imola was the key node on the trade route from Florence to the Adriatic—did not give an immediate, definitive answer. Sixtus took this delay as an insult and instead took the loan from the Pazzi bank, Florence’s principal rivals to the Medici, at the same time dismissing the Medici from the lucrative management of the papal accounts and transferring that role to the Pazzi.

The Pazzi were Florence’s second-wealthiest family, and the only ones whose banking network even approached the reach of the Medici bank. Unlike the Medici, they were of noble lineage. One of their ancestors was the first to scale the walls of Jerusalem during the First Crusade and brought back three flints from the Holy Sepulchre as a reward. Every Holy Saturday night, when fires at home were extinguished, these three stones were used to light the new flame in the cathedral, which every Florentine family then took home from the new Easter candle. Their family chapel in the courtyard of Santa Croce was built by Brunelleschi himself. All of this likely added to their resentment that a merchant family from a mountain village ruled over them.

When someone has done a great wrong to you, then he hates you with deadly intensity. After Sixtus’s elephantine moves, he felt that Lorenzo de’ Medici stood in the way of all his ambitions, and this gave birth to another ambition: that Lorenzo had to be removed from the scene.

The timing was perfect: the Duke of Milan had been murdered, leaving a minor heir and turning the duchy into a lame duck, while Venice was tied up in war with the Ottomans at sea. This was the ideal moment to strike at a Florence left unsupported.

It is unclear who initiated the conspiracy—the pope or Francesco de’ Pazzi, the one after whom the affair is named. But it hardly matters: evildoers eventually find each other. Giovanni Battista Montesecco, commander of the papal guard—whose task was to assassinate Lorenzo but who refused, saying he would not act during Mass, leaving the role to two clumsy priests who bungled the strike—gave a confession in prison before his execution, which was then printed in the first Florentine press, established a year earlier, making it one of the very first Florentine printed works. In it, he shifts the blame onto his already-hanged accomplices, Francesco de’ Pazzi, the head of the Pazzi house, and Archbishop Francesco Salviati, while subtly hinting that the pope had approved the affair. He could say no more, fearing for his family. But let’s be honest: if the conspirators were mostly the pope’s nephews, the armed security was led by the commander of his own guard, and at the same time his nephew’s father-in-law, Federigo da Montefeltro, along with his closest ally, King Ferrante of Naples, had deployed armies along Florence’s eastern and southern borders, it does not take a political genius to point at the princeps consilii or clever mastermind. The Pazzis, visibly, got tangled in the plot like Pilate in the creed: the pope needed a local figure who hated their rival, the Medici, enough to carry the blame, and that’s exactly what happened.

In his bestseller L’enigma Montefeltro. Arte e intrighi dalla congiura dei Pazzi alla Cappella Sistina (The Montefeltro Code: Art and Intrigue from the Pazzi Conspiracy to the Sistine Chapel, 2008), Marcello Simonetta describes the discovery of a previously unpublished, ciphered letter by Federigo da Montefeltro, which the author deciphered using a codebook written by his own Renaissance ancestor. In the letter to the pope, Federigo endorsed the Pazzis’ violent takeover of Florence well before the assassination attempt, reasoning that they would be far easier to influence. The letter thus provides a key to the conspiracy’s high-level political context and the pope’s role.

In his bestseller L’enigma Montefeltro. Arte e intrighi dalla congiura dei Pazzi alla Cappella Sistina (The Montefeltro Code: Art and Intrigue from the Pazzi Conspiracy to the Sistine Chapel, 2008), Marcello Simonetta describes the discovery of a previously unpublished, ciphered letter by Federigo da Montefeltro, which the author deciphered using a codebook written by his own Renaissance ancestor. In the letter to the pope, Federigo endorsed the Pazzis’ violent takeover of Florence well before the assassination attempt, reasoning that they would be far easier to influence. The letter thus provides a key to the conspiracy’s high-level political context and the pope’s role.

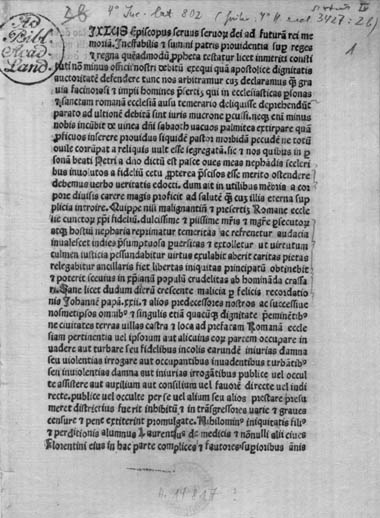

Sixtus needed time to process this unexpected turn of events. Only on June 1 did he issue a papal bull, Ineffabilis et Summi Patri providentia (“From the Unfathomable Providence of the Highest Father”), excommunicating the surviving Lorenzo and all of Florence for the murder of churchmen and continual defiance of papal authority. The bull made no mention of the conspiracy or the killings in the cathedral during Mass. During June, two further bulls were issued, offering absolution to the city if they exiled Lorenzo, or granting full indulgence to any Florentine who aided the soon-to-arrive papal troops even with a bundle of hay. These bulls thus served as an open call to civil war in Florence.

The printed version of the bull, here. In a letter to Federigo da Montefeltro, Sixtus mentions that he “sent envoys to the emperor, the kings of Hungary and Spain, etc.” for propagandistic purposes.

The printed version of the bull, here. In a letter to Federigo da Montefeltro, Sixtus mentions that he “sent envoys to the emperor, the kings of Hungary and Spain, etc.” for propagandistic purposes.

Meanwhile, the pope’s ally, King Ferrante of Naples, declared war on Florence. Federigo da Montefeltro’s army was already stationed in the east, and in the northeast, the other Sixtus nephew and lord of Imola, Girolamo Riario, had deployed his troops.

At this moment, Lorenzo de’ Medici stepped before the Signoria and delivered a speech, offering himself up to execution or exile if that would preserve the peace of the city. The Signoria rejected both options and sent a letter to the pope, defending Lorenzo and naming the true culprits. The Tuscan bishops also convened a synod, backing the Signoria’s position while issuing an excommunication decree against the pope—another of Florence’s earliest printed works. Meanwhile, Lorenzo secretly wrote to King Louis XI of France, who opposed the pope over investiture rights, and received assurances of armed support.

It was in this moment of crisis that the medal, now at the center of the Berlin exhibition, was created.

A record number of at least 19 copies of the medal survive. There were likely many more, as indicated in a letter from the foundry in Prato that produced them in bulk, addressed to Lorenzo. In other words, Lorenzo used this elite-focused medal, interpreting the event and his own role, as a form of diplomatic propaganda against the pope.

The medal was designed by Bertoldo di Giovanni, a pupil of Donatello and head of the Medici sculpture collection: a place where young Florentine sculptors, including Michelangelo, could study, copy, and work. Bertoldo had his own workshop in the Medici Palace, where he produced the master copies, while mass production was entrusted to an external—here, Prato-based—company.

The iconography of the medal is unusual, reflecting Lorenzo’s strong involvement. Typically, the obverse shows the patron’s profile, and the reverse depicts the allegorical interpretation of the event. Here, uniquely, the two sides mirror each other.

Both sides build their narrative in three bands. The lowest band shows the assassination, the middle the octagonal sanctuary of the Florence Cathedral, and the top band the portrait of one of the Medici brothers.

On the obverse crowned with Giuliano’s portrait, the left side of the lower band shows the two assassins—Francesco de’ Pazzi and Bandini—attacking Giuliano. On the right, the victim lies on the ground, and Francesco repeatedly plunges his dagger into him. The conspiracy seems victorious. Above the scene in the church floats the inscription LUCTUS PUBLICUS, “public mourning.”

On the right edge of the reverse, Bandini wounds Lorenzo with a raised sword. Lorenzo, however, vaults over the sanctuary railing, and at the center we see him wearing a beret (was it customary to keep hats on inside the church?). The ceremony continues as if nothing happened, yet we know our hero survived. This is reflected in the floating inscription: SALUS PUBLICA, “the public good.”

The salus publica motto is antique, appearing on imperial coins to celebrate great deeds for the public benefit. To the right of the sanctuary stands a statue of the goddess Salus raising a wreath. Lorenzo’s father had also used this motto on Donatello’s Judith when he survived an earlier Pazzi plot. Lorenzo echoed this in his speech before the Signoria, declaring his willingness to die or go into exile for the sake of the common good.

From the perspective of self-fashioning, this motto conveys that Lorenzo was preserved for the community by divine providence, the Christian equivalent of the ancient Salus. And just as the other side mourns the citywide favorite Giuliano under the LUCTUS PUBLICUS inscription, here the community attributes Lorenzo’s survival to divine care. It’s a clever riposte to the papal excommunication bull titled “From the Providence of the Supreme Father…”.

As Pollard writes, the medal is a “crisis genre.” It is usually created in situations that are still fluid, without a widely accepted interpretation. In such moments, an actor can offer a reading of events through the medal, and convincingly spread that interpretation among the decision-making elite—as Lorenzo did with this medal.

How successful Lorenzo’s medal-driven propaganda campaign was in European courts can only be inferred from later developments—which I won’t go into in this already lengthy post. Stay tuned.

To conclude and highlight the topic, I’d like to present one—or rather two—closely related medals.

On April 26, almost all the conspirators were captured and killed. Some were delayed: mercenary commander Montesecco could finish his confession in the prison. Jacopo de’ Pazzi hid around the city for a few days, and when found, he was torn apart in the Signoria square. Only one managed to escape the reach of Italian justice to Constantinople: Bernardo Bandini, the first to stab Giuliano.

On April 26, almost all the conspirators were captured and killed. Some were delayed: mercenary commander Montesecco could finish his confession in the prison. Jacopo de’ Pazzi hid around the city for a few days, and when found, he was torn apart in the Signoria square. Only one managed to escape the reach of Italian justice to Constantinople: Bernardo Bandini, the first to stab Giuliano.

For complete vengeance, Bandini had to be brought back to Florence. Lorenzo entered into diplomatic contact with the Sultan, and by 1478 an Ottoman embassy visited Florence. Early in 1479, Bandini was handed over to the Florentines and hanged on the Signoria window grill, like the others, still wearing the Turkish-style – “alla turchesa” – clothing in which he had been hiding. As with the earlier conspirators, sketched by Botticelli, Leonardo also made studies of Bandini.

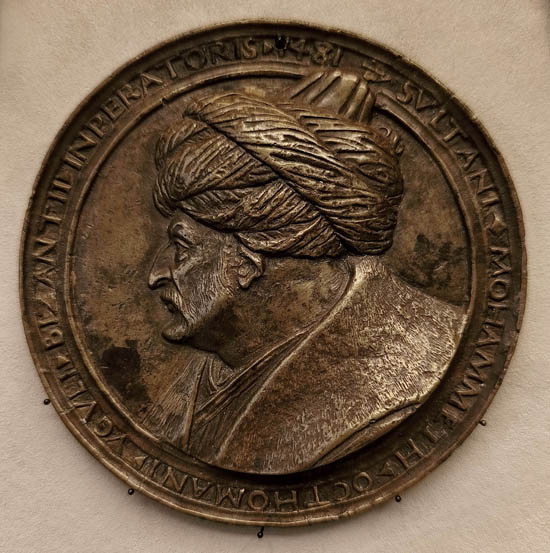

Lorenzo uniquely acknowledged the Sultan’s gesture. Knowing that Mehmed II, conqueror of Constantinople, had a keen interest in Western-style visual representation, he sent thanks and a hidden message via a medal, also designed by Bertoldo di Giovanni for this occasion.

On the obverse of the medal appears the portrait of the subject of self-fashioning, Sultan Mehmed II.

The Sultan is shown in profile, in the conventional pose of imperial coins. This medal also had a prototype, made by the Italian master Costanzo da Ferrara in the Sultan’s court in Constantinople in the 1460s.

Mehmed II actively sought out Western artists, inviting several to his court, including Gentile Bellini, who painted his famous portrait. Through Ferrara-Venice connections, Costanzo da Ferrara also arrived at the Sultan’s court.

Costanzo da Ferrara’s Western-style depiction, with a Latin inscription, was made for a Western elite audience. Sultan Mehmed wanted to convey that, after capturing Constantinople, he had become the Roman Emperor. Following the rules of Roman imperial coin portraits, he is shown in profile, gazing forward with an authoritative, assertive look. This is active self-fashioning, signaling to the West what they should expect from him.

This medal is displayed in the Bode Museum’s coin cabinet just to the right of Pisanello’s coin of John VIII, practically eye-to-eye: the city’s first Muslim ruler confronting the penultimate Christian emperor. The contrast is striking. John stares ahead with a rigid, fatalistic gaze, expecting nothing good from the future. Mehmed, in contrast, looks aggressively and powerfully toward the West, as if the entire world lies open before him, only waiting to be seized.

These two striking portraits were so well known in Italy that Piero della Francesca incorporates them in his Flagellation of Christ (1460), one layer of meaning of which reflects the mourning over Constantinople’s fall. In the figure of Pilate, John VIII observes the suffering of Christianity, orchestrated by a figure in a turban with his back turned. The turban is a copied portrait detail, with Piero transferring it from parchment to panel using pricks as guides.

Bertoldo di Giovanni’s and Lorenzo’s medal adopts this self-representation in a flattering way. Even more telling are the inscription and the reverse imagery.

The inscription names Mehmed “Emperor of Asia, Trebizond, and Greater Greece.” On the reverse, he rides a triumphal chariot over personifications of the sea and land, holding a statue of Salus or Victoria, dragging along three nude female captives representing Asia, Trebizond, and Greece.

“Asia” in contemporary terms refers to Anatolia, then mostly Greek-inhabited. Trebizond denotes the principality around present-day Trabzon, founded by Alexios Komnenos with Georgian help around the 1204 Crusader conquest of Constantinople, remaining independent until its Ottoman conquest in 1461.

But if this covers all of Greek-populated Anatolia, what is the third woman, Greece—or “Greater Greece” as the inscription says?

Today we associate Greece with the Peloponnesus and historical Macedonia, then called the Morea. But neither antiquity nor the Renaissance understood Greece this way, especially not Greater Greece. Magna Graecia from the 6th century BCE onwards referred to the Greek-settled areas of southern Italy, Sicily, and Calabria.

Lorenzo de’ Medici’s Mehmed medal, then, is partly a thank-you for the Sultan’s gesture, partly recognition of him as Roman Emperor, partly congratulation for capturing Asia Minor and Constantinople… and partly a fourth message: an invitation to take Greece or Magna Graecia (southern Italy, then part of the Kingdom of Naples), relieving Florence. Just as he secretly asked King Louis XI for military aid, he similarly requests it from the Sultan via an emblematic medal.

The Ottoman conquest of Constantinople in 1453 deeply shocked Europe. The Italian powers convened at Lodi to maintain peace. Once the shock subsided, business continued as usual. The small states continued to squander their resources against each other, allying with the Ottomans when convenient—willing even to cooperate with the devil, had they known what medal to send him.

Lorenzo’s grandfather, Cosimo, had organized a council in Florence to unite Eastern and Western Churches and send an army to defend Constantinople and Christianity, commissioning a medal so that Westerners would recognize the Byzantine ruler in exotic attire as a Roman Emperor and part of their own identity.

Lorenzo de’ Medici commissioned a medal flattering the Turkish Sultan as Roman Emperor for the benefit of his own principality. He did not care that the obverse urged Mehmed’s troops dragging away thousands of nude women from Greater Greece under Neapolitan control. What mattered was that the women were not taken by the Neapolitans from the Florentine Republic.

* * *

I am traveling in Anatolia, where during weaker periods of the Byzantine Empire, some Christian provincial lords, to preserve their own authority and spite neighboring Christian domains, willingly allied with the increasingly powerful pagan. Today, only geographic names remain of these provinces; their independent identity, let alone Christian identity, is gone.

The reason this did not happen in Italy or elsewhere in the Mediterranean did not depend on the provincial lords, equally selling themselves to the Turks, but rather on the action radius—how far the Turks could reach with contemporary military technology—and some local leaders and frontier defenders who, keeping the unity of Christianity in mind, protected their territories with total self-sacrifice against Eastern invaders.

Modern Europe is a collection of quarrelling states. Some invest beyond their means for minor gain at the expense of others; others sell out the only rescuing unity to the Eastern invaders. Will a few centuries from now we look like Anatolia?

Add comment