The gates of the dead are mentioned by Antal Szerb in Journey by Moonlight. These are narrow side doors next to the main entrance of Umbrian and Tuscan houses, often beginning a meter above ground level and usually walled up. They are only opened when a corpse has to be carried out of the house; afterwards they are bricked up again. According to Szerb, this is done so the dead person’s soul will no longer be able to find the way back into the house.

I recently wrote that these doors may have another explanation, not least because central Italian folklore doesn’t really know the motif of a harmful returning ghost. The custom may instead go back to the double doors of local Etruscan tombs. One of the tomb’s doors was the physical one, used by the living to enter the burial chamber and share a funeral banquet with the deceased. The other door was painted or carved on the back wall of the chamber, or above it, and only the dead person’s soul could pass through it. In this sense, the “gates of the dead” were originally not for leaving the house, but for entering the otherworldly dimension.

On our recent Etruscan tour we found a number of ancient examples of this.

In the Monterozzi necropolis at Tarquinia – whose roughly two hundred painted tombs form the richest pictorial archive of Etruscan mythology – a large painted door appears on the back wall of the Anina family’s tomb from the 3rd century BC. It is guarded by two underworld gatekeepers, called Charun in Etruscan, each holding a hammer. The hammer was used to open this door for the dead, just as medieval “gates of the dead” were also opened with a hammer for the coffin.

Many sarcophagi from the Monterozzi necropolis have ended up in the archaeological museum of Tarquinia. On their lids the dead usually recline on one elbow, a cup of wine in the other hand, as if taking part in their own funerary feast. The fronts of the sarcophagi are decorated with mythological scenes that symbolize death or show the Etruscan image of the afterlife. These are interpreted in detail in Lammert Bouke van der Meer’s handbook Myths and more on Etruscan stone sarcophagi (2004).

A frequent scene shows the deceased travelling to the underworld – on horseback, in a two‑wheeled chariot, or sometimes on foot – always as part of a small procession. The procession is usually led by a young woman holding a torch, lighting the dead person’s way. This is Vanth, the benevolent guide of souls, who in other scenes already stands by the dead at the very moment of death. Among the followers we often see one or two Charuns with their big hammers, ready to open the gate for the soul and then stand guard beside it.

Sarcophagus H116, from the tomb of the Camna clan, stands right at the museum entrance, as if to create a fresh example of the duality of the gates of the living and the dead. On the sarcophagus we see the gate of the underworld just as it opens before the dead man arriving on horseback. He is led by torch‑bearing Vanth and accompanied by hammer‑wielding Charun.

On sarcophagus G30, also from the Camna tomb and dated to 275–250 BC, the number of otherworldly figures doubles. The procession is both led and closed by a Vanth with a torch, and the rider is flanked by two hammer‑bearing Charuns, the first of whom leads the horse by the bridle.

On other sarcophagi the dead travel to the beyond in a biga, a two‑wheeled chariot – a privilege of the elite among the living. Here too a Charun either accompanies them or leads the horse, and on one example a clarion player brings up the rear, clearly marking the deceased as an aristocrat.

But the strangest sarcophagus belongs to someone whose name we actually know.

The recumbent figure on sarcophagus H111 holds a large scroll bearing the longest continuous text we have in Etruscan. From this we learn that the deceased was Laris Pulenas, a member of an important Tarquinian family and a descendant of the famous Greek seer Polles, mentioned in Roman literature. He himself practiced hepatoscopy – divination from entrails – and wrote a book about it. He was priest of the underworld spirits Catha, Pacha and Culsu, for whom he built a temple and set up statues. He also served on the Tarquinian magistracy, which is why the museum calls his monument the “Sarcophagus of the Magistrate”.

In the middle of his sarcophagus the two Charuns flank him with raised hammers, just as they frame the painted door in the Anina tomb. The door itself is not shown here, but at the feet of the right‑hand Charun we see a heap of stones, which in sarcophagus scenes marks the boundary of the underworld. The dead man has already crossed it; he is on the other side. The two Vanths framing the scene no longer lead a procession, but stand facing the viewer, without torches.

But where are the doors on which these hammer‑bearing figures are knocking?

The necropolis of Castel d’Asso, a few kilometres west of Viterbo, is one of the best‑preserved Etruscan cemeteries, although it is not very large – it contains only about fifty tombs. Its romantic approach more than makes up for its modest size. A country lane winds through cabbage fields and ends in an unmarked muddy parking place, from which a footpath sets off, with a single sign noting that from here on you are on private land and only pedestrians are allowed. The necropolis itself is not mentioned.

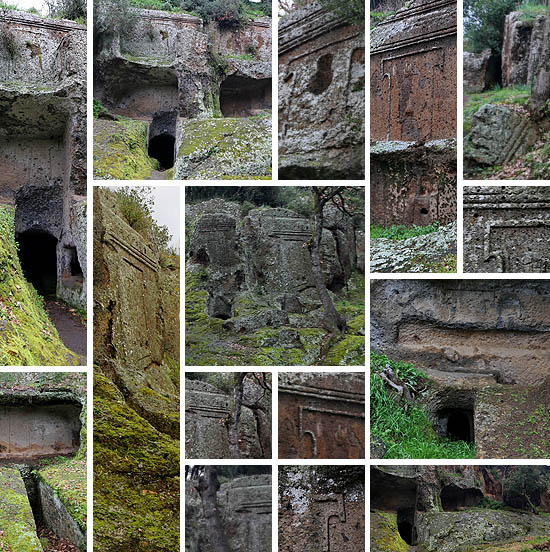

The path runs downhill. We are in a canyon, and after about two hundred metres we start seeing neatly carved cornices and smoothed facades in the rock on both sides. The fifty‑odd tombs all follow a similar layout: at the very bottom, underground, lies the burial chamber, reached by a steep stairway; above it a spacious rock‑cut hall; and above that a flat, polished rock face. On the back wall of the hall and again on the cliff face we see carefully carved outlines of doors – a smaller, human‑sized one in the hall, and above it a larger, monumental version on the cliff. These are the doors through which only the dead may pass, once Charun has opened them.

The light drizzle suits the scene perfectly: it deepens the colour of the rock, makes the moss glow bright green, and gives the landscape a romantic air. Samuel James Ainsley (1806–1874) must have seen it much the same way when he travelled the Etruscan necropoleis with George Dennis; in 1848 the British Museum published their massive volume Cities and Cemeteries of Etruria. In Ainsley’s illustration we even see an Etruscan inscription and some goats; we didn’t encounter either of those.

What we did see, though, is the ruined castle in the drawing. This is Asso, the fortress of the ancient Etruscan city of Axia – or rather, the remains of the medieval castle that later occupied the same site. Nothing survives of the city itself; it was probably destroyed in barbarian invasions. Its inhabitants live on in the necropolis, behind sealed doors where no barbarian can disturb them.

Add comment