“I would swear it is impossible to buy fresh fish in Mallorca that does not come from the sea, and some Mallorcans probably don’t even realize that in those strange, bland inland waters there might be anything edible at all.” wrote Wang Wei just a few days ago in his birthday greeting, intending to praise sea fish, but incidentally delivering a sharp jab at their freshwater cousins. The last days of the year offer a ritual opportunity to restore the honor of my scaly compatriots.

Just as a skilled interpreter knows the entire nomenclature of a Mediterranean fish market in Italian, Spanish, or Catalan, while only able to render it in Hungarian as the single word “sügér” – or “tőkehal” [cod] for northern fish – so too, the sun-drenched peoples cannot imagine the delicate distinctions made by the gloomy northern nations regarding the creatures wriggling in their muddy waters, not only in terms of pedigree but also in terms of preparation.

Take the carp, for instance, whose final honors depend on whether it comes from the Danube or the Tisza before hitting the kitchen. Without diving into the details – which would inevitably spark dogmatic and liturgical debates – it’s enough to point out a difference any layperson can spot: in Baja, the Danube fish soup is made with so-called matchstick noodles, while in Szeged, the Tisza fish soup is thickened with smaller fish before the carp goes in. And the faithful of each denomination don’t just consider their own creed more blessed—they actually regard the other’s liturgy as heretical and its accompanying agape as unfit for communion.

A Mallorcan would probably find it utterly unimaginable that under the gloomy skies of the North, along rivers flowing with ice floes, there exist specialized institutions called halászcsárda [fishermen’s tavern], where hardcore devotees gather exclusively to ritually enjoy dishes prepared according to the tastes of the local swamp-dwelling freshwater tribes. To illustrate this—while giving credit to Baja—here’s last night’s fish soup from Szeged’s Sótartó Halászcsárda. The filézett ponty [filleted carp] cooked in a bogrács [little cauldron] gets its reddish hue from édes-nemes [sweet-noble] paprika. Those craving a bit more punch can add sliced hegyes erős [hot green paprika] (not Erős Pista [“Strong Steve”, ground pickled chili, an essential for lazy Hungarian households]!!!). In the background, belsőség [“offal”, fish roe and fish milk] and friss házi kenyér [fresh homemade bread] await deployment. If the Mallorcan anthropologists adds szatmári szilva [plum brandy from Szatmár] and szekszárdi vörös [red wine from Szekszárd] or a egy korsó Dreher [a mug of Dreher beer] to this glossary, they can safely dive into the swamp’s dead and living creatures.

For instance, they might level up and order a kétembörös fatányéros [two-person wooden-platter] vegyes haltál [mixed fish plate] On the platter, representatives of Hungary’s three types of freshwater fish come together in an allegory of Thetys, proudly facing off against any Mallorcan restaurant’s Poseidon-allegory: the river-born carp, the stream-diving trout, and the lake heck. Skeptical scientists may point out that heck comes from South American seas, but in ritual matters, faith matters—and every Hungarian believes that heck grows in Lake Balaton if it reaches its peak development on its shores: the state of roasted heck.

I emphasize the ritual nature of freshwater fish consumption for a reason. Landlocked peoples consume it on truly ritual occasions: when visiting Szeged (or Baja), Paks, Kalocsa, Horány, or other sanctuaries of this creed, as well as during year-end holidays. Before the Second Vatican Council (1962–65), in Catholic countryside, Christmas was preceded by a forty-day fast similar to Lent, ending only after Christmas midnight mass—so the Christmas dinner featured carp, which was permissible during the fast.

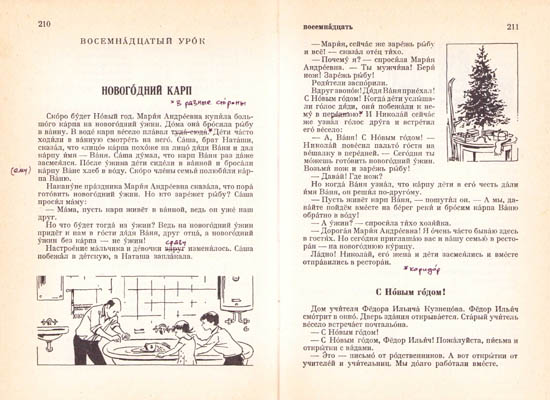

In Russia, where Christmas is celebrated in the New Year, carp is ritually eaten at the New Year’s dinner. This is the subject of the reading from the Hungarian “Let’s Learn Languages” series’ Russian textbook from the 1980s. Now that I’ve reread it, the book is a real time machine, transporting you to a utopian world where Soviet engineers visit Hungarian factories to teach local engineers reverently listening to them, and young workers, dressed up for the occasion, head to the cinema—of course to see a new Soviet film—or to the Youth Park. Now I truly understand why, if learning a language also means learning a culture, and conversely, rejecting a culture also rejects its language—no one here mastered Russian during eight or twelve years of compulsory Russian lessons.

New Year is just around the corner! Mariya Andreyevna bought a hefty carp for the New Year’s dinner. At home, she let the fish loose in the bathtub [as many Hungarian families also used to do]. The carp happily swam up and down. The children often went into the bathroom to check on him. Sasha, Natasha’s older brother, said that the carp’s face reminded him of Uncle Vanya, and named him Vanya. Sasha even thought he saw Vanya the carp smile once. After dinner, the kids went back to the bathroom, tossing pieces of bread to Vanya the carp. The family soon grew fond of Vanya.

On the eve of the holiday, Mariya Andreyevna declared it was time to prepare the New Year’s dinner. But who would kill the fish? Sasha asked:

– Mama, let the carp live in the bathroom—it’s our friend now.

But what about dinner? Uncle Vanya, Papa’s friend, was coming over, and a New Year’s dinner without carp isn’t really a dinner!

The little boy and girl’s moods instantly changed. Sasha ran to the nursery, and Natasha burst into tears.

– Mariya, just cut the fish now and that’s it, – said Papa quietly.

– Why me? – asked Mariya Andreyevna. – You’re the man! Take the knife and do it.

The parents started bickering.

But the doorbell rang. Uncle Vanya had arrived! Happy New Year! When the kids heard his voice, they ran to the hallway to greet him. Nikolay immediately recognized his friend’s voice too and cheerfully said:

– Ah, Vanya! Happy New Year! – He hung the guest’s coat on the hall rack. – Tonight you can prepare the New Year’s dinner. Take the knife and cut the fish.

– Let’s go. Where’s the knife?

But when Vanya learned that the children had named the carp after him, he changed his mind.

– Let Vanya the carp live, – he said. – Let’s go to the river and release him back.

– And what about dinner? – asked the hostess softly.

– Dear Mariya Andreyevna! I’ve been your guest so many times. Tonight, I’ll treat you to a restaurant dinner—New Year’s roast chicken.

That’s it! Nikolay, his wife, and the children laughed together and set off to the restaurant.

And what did they eat at the restaurant? Uncle Vanya suggested chicken, but who knows—it’s quite possible that, freed from the ritual duty of carp, they enjoyed something truly delicious and rare—a sea fish.

Add comment